CUDA Architecture

The slides accompanying these lecture notes can be found here.

Architecture

A GPU consists of chip that is composed of several streaming multiprocessors (SMs). Each SM has a number of cores that execute instructions in parallel. The H100, seen below, has 144 SMs (you can actually count them by eye). Each SM has 128 FP32 cores for a total of 18,432 cores. Historically, CUDA has used DDR memory, but newer architectures use high-bandwidth memory (HBM). This is closely integrated with the GPU for faster data transfer.

In the image below, you can see 6 HBM3 memory modules surrounding the GPU, 3 on either side of the die. HBM3 is capable of 3 TB/s of bandwidth. The platform shown only uses 5 of these modules. The full version will utilize all 6.

).](/ox-hugo/2024-01-11_14-29-08_screenshot.png)

Figure 1: NVIDIA H100 GPU with 144 SMs (NVIDIA).

Block Scheduling

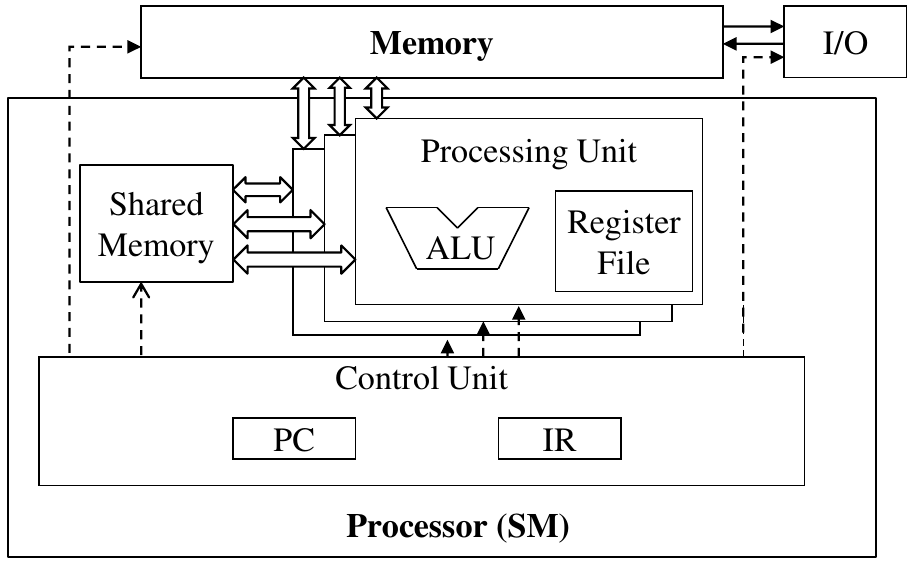

When a kernel is launched, the blocks that we configure in our code are assigned to SMs. All threads in each block will be assigned to each SM. Depending on the platform, the number of blocks that can be assigned to an SM will vary. This is discussed in more detail below. Since all threads in a block are on the same SM, they can share data and communicate with each other.

Synchronization

Threads that run on the same block can be synchronized using __syncthreads(). This is a pretty straightforward concept, but it is important to understand the caveats. When a kernel reaches this call, the execution of the threads will stop until all of them have reached that point. This construct is typically used when threads need to share data or are dependent on the results of other threads.

Be careful on using this call. An example of incorrect usage is shown below.

__global__

void kernel(int *a, int *b, int *c) {

if (threadIdx.x % 2 == 0) {

// Perform some work

__syncthreads();

else {

// Perform some other work

__syncthreads();

}

}

Unlike a general-purpose processor, a GPU does not have control hardware for each individual core. This means that all threads must execute the same instructions using shared resources. In the example above, it is possible for some threads to branch off into a different part of the program. However, only one of the paths can be executed based on this limitation. This is called control divergence and is discussed in more detail below.

Even though the call looks the same, each __syncthreads() is different. The first call will only synchronize the threads that executed the first path. The second call will only synchronize the threads that executed the second path. The result is either undefined output or a deadlock, in which the threads will never reach the second call.

Since threads in separate blocks cannot be synchronized, the blocks can be executed in any arbitrary order. You might immediately ask yourself how a complex problem that requires synchronization between all parts of the data can get around this limitation. We will explore more complex patterns and their solutions in later sections.

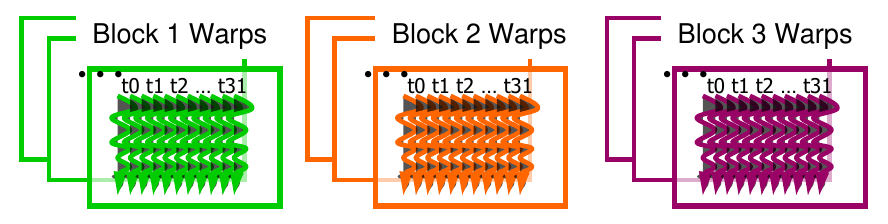

Warps

Streaming Multiprocessors in a CUDA chip execute threads in a group of 32 called warps. Since Compute Capability 1.0, the warp size has not changed. When a block is assigned to an SM, it is divided into warps. Given this size, you can easily determine the number of warps assigned to an SM. For example, if you have a block of 256 threads, the SM has 256 / 32 = 8 warps. If the block size is not evenly divisible by the number of warps per SM, the last warp will be padded with inactive threads.

When multi-dimensional thread blocks are assigned to an SM, the threads are linearly mapped in a row-major order before being partitioned into warps. For example, a 2D block of \(16 \times 16\) threads will be mapped to a 1D array of 256 threads. The first 32 threads will be assigned to the first warp, the next 32 to the second warp, and so on.

Warps are executed following the Single-Instruction, Multiple-Data (SIMD) model. There is a single program that runs the same instruction on all threads in the same order. If a thread would have executed a different path based on its input data, it would not be executed with the others. This is called control divergence and is explained in the next section.

The advantage of this model is that more physical space can be dedicated to ALUs instead of control logic. In a traditional CPU, each processing core would have its own control logic. The tradeoff is that different cores can execute their own programs at varying points in time.

Clarification on Warps, FP Cores, and Blocks

As stated above, the H100 has 128 FP cores per SM, the warp size is 32, the maximum number of threads per block is 1024, and the maximum number of threads per SM is 2048. Each SM can execute instructions for a number of warps defined by the specific architecture. The scheduler will assign warps to actual processing cores.

Control Divergence

Since a traditional CPU has separate control logic for each core, it can execute different programs at the same time. If the program has a conditional statement, it does not need to worry about synchronizing instructions with another core. This is not the case with a GPU. Since every thread in a warp executes the same instruction, only threads that would execute the same path can be processed at the same time. If a thread would execute a different path, it is not executed with the others. This is called control divergence.

What exactly happens then if a warp has 32 threads of which only 16 would execute the same path? Simply, multiple passes are made until all possible paths of execution are considered based on the divergence of the threads. The SM would process the first 16 threads that all follow the same path before processing the second 16 threads.

This also applies to other control flow statements such as loops. Consider a CUDA program that processes the elements of a vector. Depending on the loop and data used, the threads may execute a different number of iterations. As threads finished their iterations, they would be disabled while the remaining threads continue.

There are some cases in which it is apparent that your program will exhibit control divergence. For example, if you have a conditional statement based on the thread index, you can be sure that the threads will execute different paths.

Example

Consider a \(200 \times 150\) image that is processed by a CUDA program. The kernel is launched with \(16 \times 16\) blocks which means there are \(200 / 16 = 13\) blocks in the x-direction and \(150 / 16 = 10\) blocks in the y-direction. The total number of blocks is \(13 \times 10 = 130\). Each block has 256 threads, or 8 warps. That means that the total number of warps is \(130 \times 8 = 1040\).

Warp Scheduling

An SM can only execute instructions for a small number of warps. The architecture allows for more warps than the SM can execute since warps will often be waiting for some result or data transfer. Warps are selected based on a priority mechanism. This is called latency tolerance.

Zero-overhead thread scheduling allows for selecting warps without any overhead. A CPU has more space on the chip for caching and branch prediction so that latency is as low as possible. GPUs have more floating point units and can switch between warps, effectively hiding latency.

The execution states for all assigned warps are stored in the hardware registers, eliminating the need to save and restore registers when switching between warps.

Under this model, it is ideal for an SM to be assigned more threads than it can execute at once. This increases the odds that the SM will have a warp ready to execute when another warp is waiting for data.

Resource Partitioning

There is a limit on the number of warps that an SM can support. In general, we want to maximize the throughput of an SM by assigning as many warps as possible. The ratio of warps assigned to the number of warps an SM supports is called occupancy. If we understand how the architecture partitions the resources, we can optimize our programs for peak performance. Consider the NVIDIA GH100 GPU, pictured below.

).](/ox-hugo/2024-01-11_11-44-01_screenshot.png)

Figure 4: GH100 Full GPU with 144 SMs (NVIDIA).

The H100 architecture shares the same limitations in compute capability as the A100, so this example will follow the book closely (NO_ITEM_DATA:hwu_programming_2022). The H100 supports 32 threads per warp, 64 warps per SM, 32 blocks per SM, and 2048 threads per SM. Depending on the block size chosen, the number of blocks per SM will differ. For example, a block size of 256 threads means that there are 2048 / 256 = 8 blocks per SM. This block size would maximize occupancy since the architecture supports more than 8 blocks per SM. Also, the number of threads per block is less than the limit of 1024.

What if we chose 32 threads per block? Then there would be 2048 / 32 = 64 blocks per SM. However, the device only supports 32 blocks per SM. With only 32 blocks allocated with 32 threads per block, a total of 1024 threads would be utilized. The occupancy in this case is 1024 / 2048 = 50%.

Historically, NVIDIA provided an excel spreadsheet to compute occupancy. It has since been deprecated in favor of Nsight Compute, a tool that provides more information about the performance of your program. We will cover this tool in a later section.

Including Registers

Another factor for occupancy is the number of registers used per thread. The H100 has 65,536 registers available for use. As long as your program does not use more than this, you can follow the simpler occupancy calculation from above. With 2048 threads, that leaves 65,536 / 2048 = 32 registers per thread. If we run a program with 256 threads/block, there would be 2048 / 256 = 8 blocks per SM. This means that there are 8 * 256 = 2048 threads per SM. With 31 registers per thread, the total number of registers used per SM is 2048 * 31 = 63,488. In this case we still maximize occupancy since 63,488 < 65,536.

What if each thread required 33 registers? In that case, the total number of registers used per SM would be 2048 * 33 = 67,584. How would these resources be partitioned? Only 7 blocks could be assigned since 7 * 256 * 33 = 59,136 < 65,536. This means that only 7 * 256 = 1792 threads would be used, reducing the occupancy to 1792 / 2048 = 87.5%.

Dynamic Launch Configurations

Depending on our application requirements, we may need to support a range of devices across several compute capabalities. The CUDA API makes this simple by providing several different functions for querying device properties. These can be called from the host before configuring and launching a kernel. This is not an exhaustive list, but it covers the most important properties. When we first launch a program that utilizes CUDA, we will want to know how many devices are available. Later in this course, we will develop programs that utilize multiple GPUs, but we would also want our code to adapt dynamically to a single GPU.

int deviceCount;

cudaGetDeviceCount(&deviceCount);

Once the device count is known, the properties of each device can be acquired with cudaGetDeviceProperties. This function takes a pointer to a cudaDeviceProp struct. The struct contains several properties that can be used to configure the kernel launch. The most important properties are listed below. A full list can be found in the CUDA documentation.

| Property | Description |

|---|---|

name |

Name of the device |

totalGlobalMem |

Total amount of global memory available on the device in bytes |

sharedMemPerBlock |

Shared memory available per block in bytes |

regsPerBlock |

32-bit registers available per block |

warpSize |

Warp size in threads |

maxThreadsPerBlock |

Maximum number of threads per block |

maxThreadsDim |

Maximum size of each dimension of a block |

maxGridSize |

Maximum size of each dimension of a grid |

multiProcessorCount |

Number of SMs on the device |

maxThreadsPerMultiProcessor |

Maximum number of threads per SM |

The following example iterates through all devices and queries their properties.

for (int i = 0; i < deviceCount; i++) {

cudaDeviceProp prop;

cudaGetDeviceProperties(&prop, i);

// Use properties to configure kernel launch

}

The Takeaway

The CUDA architecture is designed to maximize the number of threads that can be executed in parallel. This is achieved by partitioning the resources of the GPU into SMs. Each SM can execute a small number of warps at a time. The number of warps that can be assigned to an SM is called occupancy. The occupancy is determined by the number of threads per block, the number of blocks per SM, and the number of registers used per thread. The CUDA API provides functions for querying device properties so that the kernel launch can be configured dynamically.