Fine-Tuning LLMs

After pre-training an LLM, which builds a general model of language understanding, fine-tuning is necessary to adapt the model to behave like a helpful assistant.

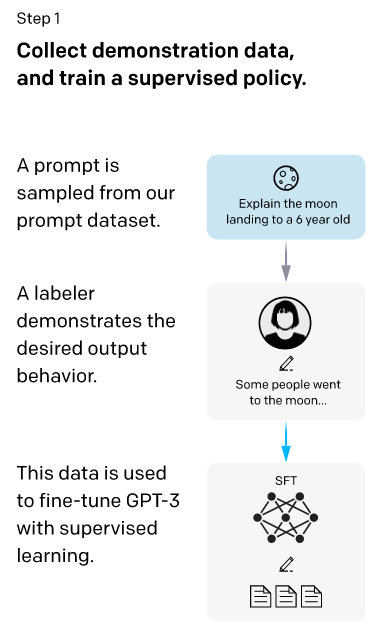

Supervised Fine-Tuning

The first form of post-training is Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT). This requires annotated examples of prompts and responses that demonstrate how the model should behave when responding to user input.

Figure 1: SFT pipeline (Ouyang et al. 2022).

These datasets are much more expensive to create since they require more thought in the quality of prompts and responses. Pre-training may be cheap with regards to annotation, but it is expensive in the cost of curation and compute. SFT is cheap in terms of compute but requires expensive annotations.

It is impossible to create a dataset with every conceivable question and answer. Instead, the model only needs to mimic the style of responses seen in the dataset. An open source dataset for SFT can be viewed here.

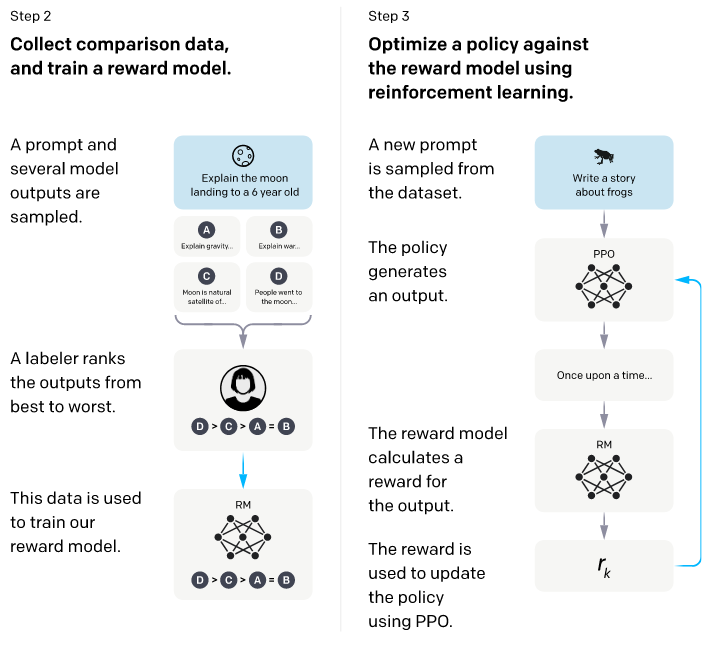

Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback

Reinforcement learning is used to improve the quality of responses from an LLM. Instead of requiring a human annotator to provide ideal responses to all conceivable prompts, they only need to train a model to mimic their preferences. This is typically done after the SFT stage.

Figure 2: RLHF pipeline (Ouyang et al. 2022)

This type of training was also applied to text summarization, where a human annotator would rate the best summarization provided from a model (Stiennon et al. 2022).

In recent models, it is common to have a previous checkpoint generate prompts and responses that are then evaluated by a human annotator (DeepSeek-AI et al. 2025). Llama 3 uses a mixture of human annotations with synthetic data (Dubey et al. 2024).

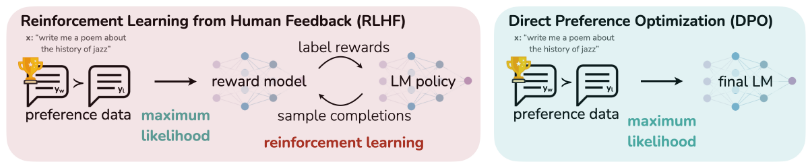

Direct Preference Optimization

RLHF has proven effective for fine-tuning models to provide high quality and accurate responses. However, the additional training required can be replaced by Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) (Rafailov et al. 2024). In this work, the preference data is input directly into the model and trains it using a simple classification objective.

Figure 3: RLHF vs. DPO (Rafailov et al. 2024)

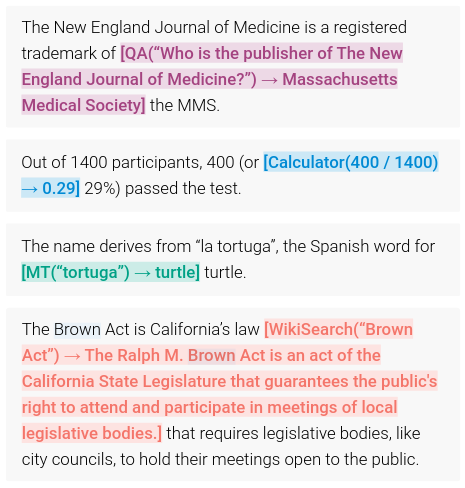

Using Tools

Adding tool use expands the capabilities and accuracy of LLMs on a wide range of tasks. For example, being able to verify information reduces the likelihood of hallucinations and general misinformation. Models can adapt to tool use via self-supervised learning, where a few examples of the tools and how to use them are all that is needed (Schick et al. 2023).

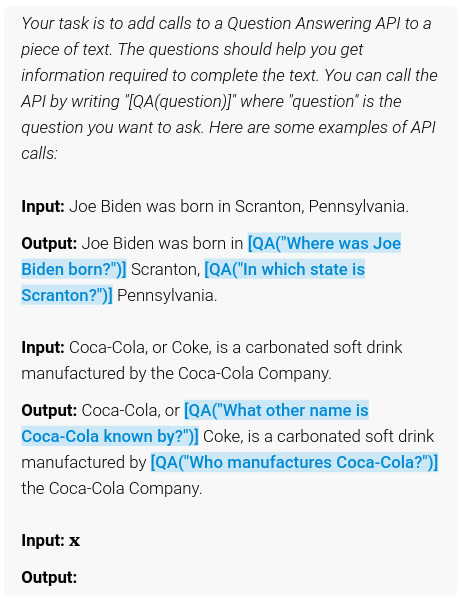

Figure 4: Examples of tool use predictions (Schick et al. 2023).

A small dataset of prompts is created which includes example behavior and special syntax for calling and executing tools. This is also known as few-shot learning (Brown et al. 2020), a capability that LLMs already have from pre-training. Unique prompts are required for each tool.

Figure 5: Example few-shot prompt for tool use (Schick et al. 2023).

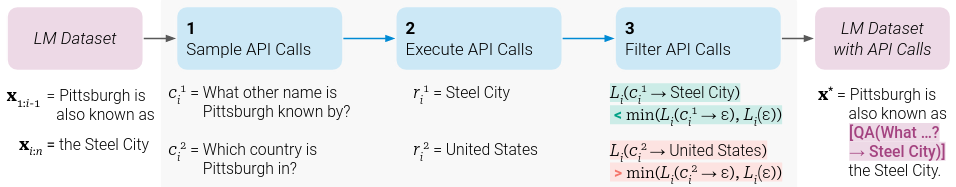

Once the model has examples of which tools are available and how to use them, it can sample positions from input text and generate API calls to the tools. The result is then evaluated using a loss function. If the loss is not reduced, the tool call is filtered out.

Figure 6: Self-supervised pipeline of Toolformer (Schick et al. 2023).

Chain of Thought (CoT) and Reasoning

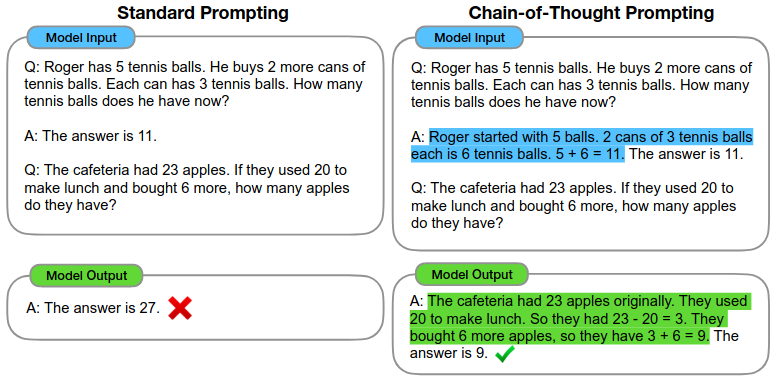

It has been shown that prompting a model to explain its calculations lead to higher accuracy on a variety of tasks (Wei et al. 2023), (Chung et al. 2022). This type of instruction is facilitated through in-context learning on example prompts.

Figure 7: Example of CoT prompting (Wei et al. 2023).

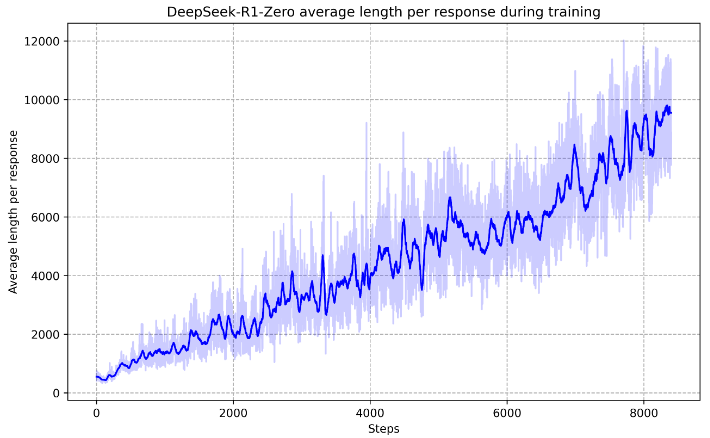

CoT prompts elicit reasoning behaviors in LLMs. To train a model to exhibit more reasoning on complex tasks, a reward model was employed which provides a higher reward when the model produces longer responses. As opposed to traditional RLHF, where the output is subjective and is only rated against human preferences, verifiable data is used for training. This allows the model to immediately determine if it was correct or not (DeepSeek-AI 2025).

Figure 8: The reward model encourages longer responses when solving complex tasks (DeepSeek-AI 2025).