GPU Pattern: Merge

Key Concepts and Challenges

- Dynamic input data identification

- Data locality

- Buffer management schemes

Introduction

The merge operation takes two sorted subarrays and combines them into a single sorted array. You may be familiar with this approach from studying Divide and Conquer Algorithms. Parallelizing the merge operation is a non-trivial task and will require the use of a few new techniques.

The Merge Operation

The specific parallel merge operation studied in these notes is from “Perfectly load-balanced, optimal, stable, parallel merge” (Siebert and Träff 2013). Their approach works by first computing which values are needed in each merge step, and then using a parallel kernel to compute the merge. These steps can be computed by each thread independently.

Co-rank Function

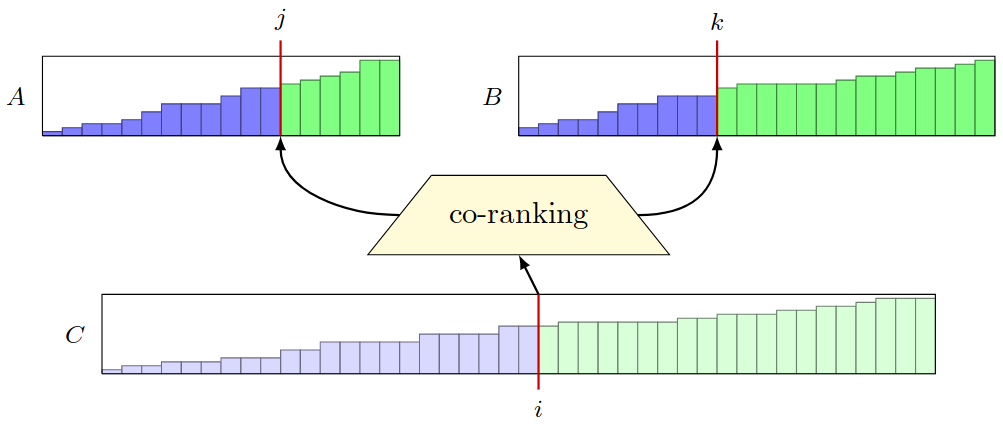

The key to the parallel merge algorithm reviewed in these notes is the co-ranking function (Siebert and Träff 2013). This function computes the range of indices needed from the two input values to produce a given value in the output array, without actually needing to merge the two input arrays.

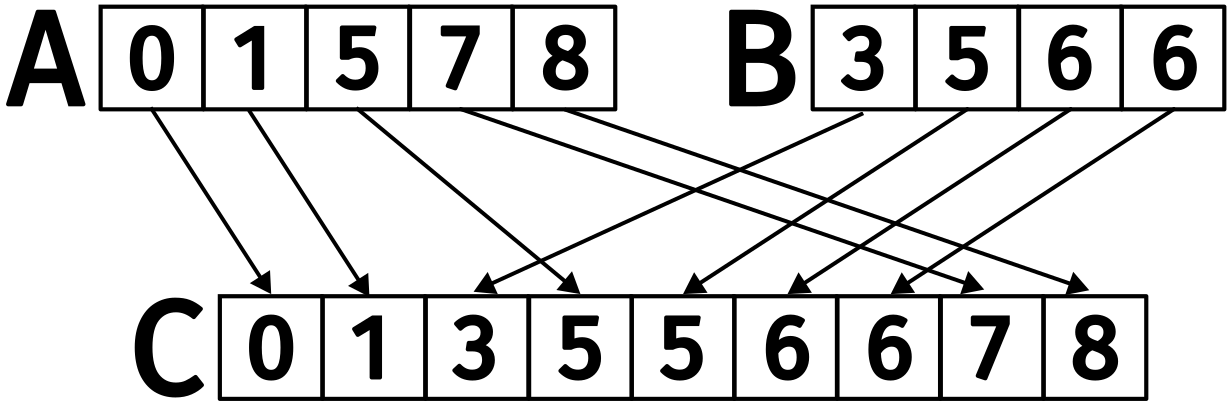

When merging two sorted arrays, we can observe that the output index \(0 \leq k < m + n\) comes from either \(0 \leq i < m\) from input \(A\) or \(0 \leq j < n\) from input \(B\).

In the figure above, the element at \(k = 3\) comes from \(A[2]\), so \(i = 2\). It must be that \(k=3\) is the result of merging the first \(i=2\) elements of \(A\) with the first \(j=k - i\) elements of \(B\). This works both ways: for \(k=6\), the value is taken from \(B[3]\), so \(j=3\), and the result is the merge of the first \(i=k-j\) elements of \(A\) with the first \(j=3\) elements of \(B\).

An efficient method for computing the co-rank function follows the first lemma put forth in (Siebert and Träff 2013):

Lemma 1. For any \(k, 0 \leq k < m + n\), there exists a unique \(i, 0 \leq i \leq m\), and a unique \(j, 0 \leq j \leq n\), with \(i + j = k\) such that

- \(i = 0\) or \(A[i-1] \leq B[j]\) and

- \(j = 0\) or \(B[j-1] < A[i]\).

Figure 2: Co-rank function visualization (Siebert and Träff 2013).

Implementation

Given the rank \(k\) of an element in an output array \(C\) and two input arrays \(A\) and \(B\), the co-rank function \(f\) returns the co-rank value for the corresponding element in \(A\) and \(B\).

How would the co-rank function be used in the example above? Given two threads, let thread 1 compute the co-rank for \(k=4\). This would return \(i=3\) and \(j=1\). We quickly verify that this passes the first lemma stated above.

\[ A[2] = 5 \leq B[1] = 5$ and $B[0] = 3 < A[3] = 7. \]

Code for the co-rank function is given below. Since the input arrays are already sorted, we can use a binary search to find the co-rank values.

int co_rank(int k, int *A, int m, int *B, int n) {

int i = min(k, m);

int j = k - i;

int i_low = max(0, k-n);

int j_low = max(0, k-m);

int delta;

bool active = true;

while (active) {

if (i > 0 && j < n && A[i-1] > B[j]) {

delta = (i - i_low + 1) / 2;

j_low = j;

i -= delta;

j += delta;

} else if (j > 0 && i < m && B[j-1] >= A[i]) {

delta = (j - j_low + 1) / 2;

i_low = i;

j -= delta;

i += delta;

} else {

active = false;

}

}

return i;

}

Consider running a merge kernel across 3 threads where each thread takes 3 sequential output values. Use the co-rank function to compute the co-rank values for \(k=3\) and \(k=6\), simulating the tasks for the second and third threads. The values for \(k=3\) should be \(i=2\) and \(j=1\), for reference. All values below these indices would be used by the first thread.

Parallel Kernel

We can now implement a basic parallel merge kernel. Each thread is responsible for determining how many elements it will be responsible for merging. The range of input values is determined via two calls to co_rank, one for the starting and ending point.

__global__ void merge_basic_kernel(int *A, int m, int *B, int n, int *C) {

int tid = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

int elementsPerThread = ceil((m + n) / (blockDim.x * gridDim.x));

int k_curr = tid * elementsPerThread; // start output index

int k_next = min((tid + 1) * elementsPerThread, m + n); // end output index

int i_curr = co_rank(k_curr, A, m, B, n);

int i_next = co_rank(k_next, A, m, B, n);

int j_curr = k_curr - i_curr;

int j_next = k_next - i_next;

merge_sequential(&A[i_curr], i_next - i_curr, &B[j_curr], j_next - j_curr, &C[k_curr]);

}

Two major issues should be clear from the code above. First, the memory being accesses is not coalesced. The binary search in co_rank also means that the memory access pattern is less than ideal. Since the main issue in both cases relates to memory efficiency, we should look at tools that address memory access patterns.

Tiled Merge

The memory access pattern is sparse and thus does not take advantage of coalescing. We can improve upon this by having the threads transfer data from global memory to shared memory in a coalesced manner. That way the higher latency operation will be coalesced. The data in shared memory may be accessed out of order, but the latency is much lower.

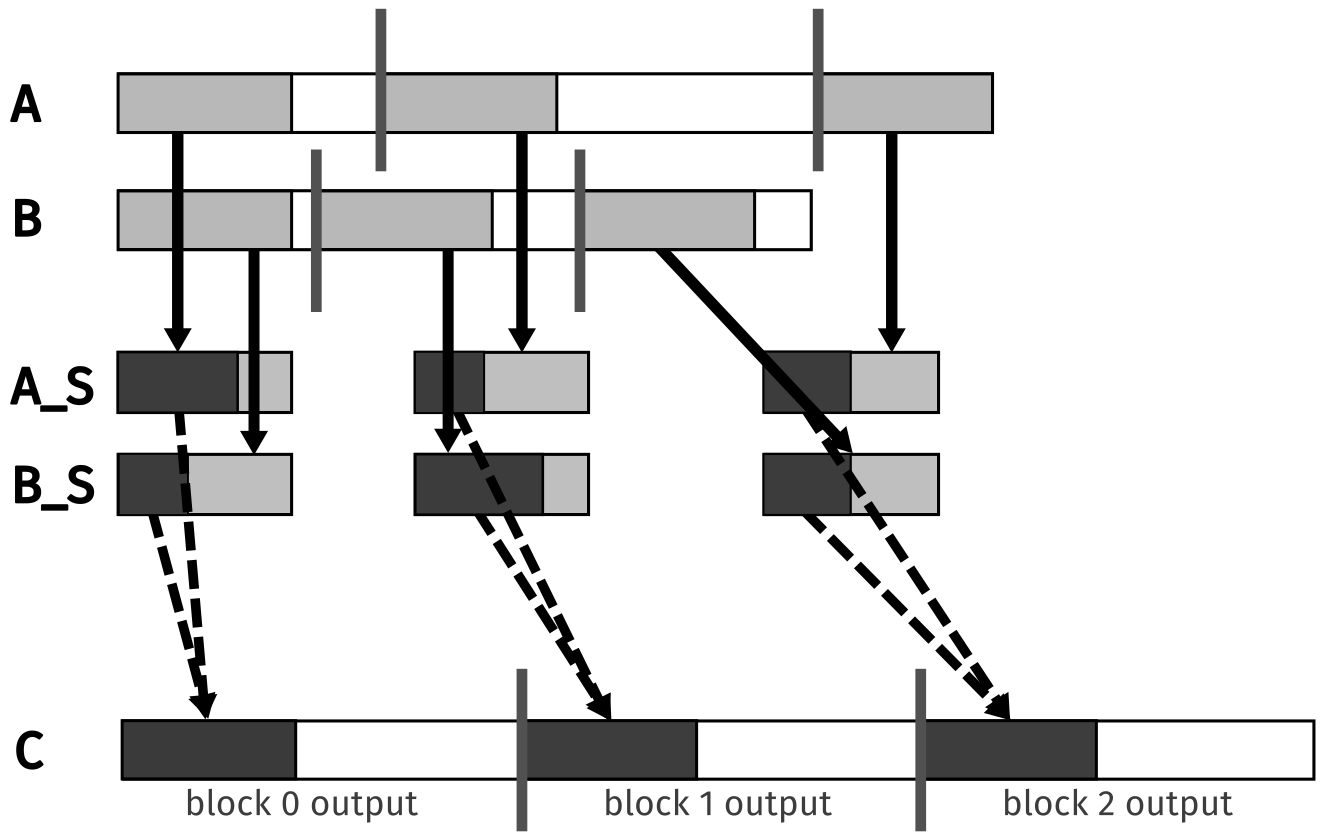

The subarrays from \(A\) and \(B\) that are used by adjacent threads are also adjacent in memory. By considering block-level subarrays, we can ensure that the data is coalesced. This is the idea behind the tiled merge algorithm. The figure below visualizes this concept.

Figure 3: Design of a tiled merge kernel (recreated from (Hwu, Kirk, and El Hajj 2022)).

The shared memory blocks \(A_s\) and \(B_s\) obviously cannot store the entire range of data needed. In each iteration, the threads in a block will load a new set of data from global memory to shared memory. The light gray section of the block from \(A\) and \(B\) are loaded into \(A_s\) and \(B_s\), respectively. If they collectively load \(2n\) elements, only \(n\) elements will be used in the merge operation. This is because in the worst case, all elements going to the output array will come from one of the two input arrays. See the exercise at the end of this section for a more detailed explanation.

Each block will use a portion of both \(A_s\) and \(B_s\) to compute the merge. This is shown with dotted lines going from the shared memory to the output array.

Part 1

The code below shows the first part of the tiled merge kernel.

__global__ void merge_tiled_kernel(int *A, int m, int n, int *C, int tile_size) {

extern __shared__ int shareAB[];

int *A_s = &shareAB[0];

int *B_s = &shareAB[tile_size];

int C_curr = blockIdx.x * ceil((m+n)/gridDim.x);

int C_next = min((blockIdx.x+1) * ceil((m+n)/gridDim.x), m+n);

if (threadIdx.x == 0) {

// Block-level co-rank values will be available to all threads in the block

A_s[0] = co_rank(C_curr, A, m, B, n);

A_s[1] = co_rank(C_next, A, m, B, n);

}

__syncthreads();

int A_curr = A_s[0];

int A_next = A_s[1];

int B_curr = C_curr - A_curr;

int B_next = C_next - A_next;

__syncthreads();

The first part establishes the shared memory and the co-rank values for the block. Each thread will have access to the start and end values for input matrices \(A\) and \(B\) as well. If the kernel is just getting started, we would have that A_curr = 0, B_curr = 0, and C_curr = 0.

Part 2

The second part of the kernel is responsible for loading the input data into shared memory. This is done in a coalesced manner, as the threads in a block will load a contiguous section of the input arrays.

int counter = 0;

int C_length = C_next - C_curr;

int A_length = A_next - A_curr;

int B_length = B_next - B_curr;

int total_iteration = ceil(C_length / tile_size);

int C_completed = 0;

int A_consumed = 0;

int B_consumed = 0;

while (counter < total_iteration) {

for (int i = 0; i < tile_size; i += blockDim.x) {

if (i + threadIdx.x < A_length - A_consumed) {

A_s[i + threadIdx.x] = A[A_curr + A_consumed + i + threadIdx.x];

}

if (i + threadIdx.x < B_length - B_consumed) {

B_s[i + threadIdx.x] = B[B_curr + B_consumed + i + threadIdx.x];

}

}

__syncthreads();

Part 3

With the input in shared memory, each thread will divide up this input and merge their respective sections in parallel. This is done by calculating the c_curr and c_next first, which is the output section of the thread. Using those boundaries, two calls to co_rank will determine the input sections the thread.

int c_curr = threadIdx.x * (tile_size / blockDim.x);

int c_next = (threadIdx.x + 1) * (tile_size / blockDim.x);

c_curr = (c_curr <= C_length - C_completed) ? c_curr : C_length - C_completed;

c_next = (c_next <= C_length - C_completed) ? c_next : C_length - C_completed;

int a_curr = co_rank(c_curr,

A_s, min(tile_size, A_length - A_consumed),

B_s, min(tile_size, B_length - B_consumed));

int b_curr = c_curr - a_curr;

int a_next = co_rank(c_next,

A_s, min(tile_size, A_length - A_consumed),

B_s, min(tile_size, B_length - B_consumed));

int b_next = c_next - a_next;

merge_sequential(&A_s[a_curr], a_next - a_curr, &B_s[b_curr], b_next - b_curr, &C[C_urr + C_completed + c_curr]);

counter++;

C_completed += tile_size;

A_consumed += co_rank(tile_size A_s, tile_size, B_s, tile_size);

B_consumed = C_completed - A_consumed;

__syncthreads();

}

}

Example: Walkthrough of Kernel

Consider the following example. We have two input arrays \(A = [1, 3, 5, 7, 9]\) and \(B = [2, 4, 6, 8, 10]\). The output array \(C\) will have 10 elements. We will use 2 blocks and 4 threads per block. The tile size is 4. With 10 elements and 2 blocks, each block is responsible for 5 elements.

The main while loop will need to iterate twice to cover the entire output array. The first iteration will load the first 4 elements of \(A\) and \(B\) into shared memory. Once the data is in memory, each thread divides the input tiles by running the co-rank function on the data that is in shared memory. The computed indices are the boundaries between each thread.

In each iteration, a block is responsible for 4 elements. Given that we have 4 threads per block, each thread will be responsible for 1 output element per iteration. For thread 0 we have that c_curr = 0 and c_next = 2. This results in a_curr = 0, b_curr = 0, a_next = 1, and b_next = 1. The merge operation will then be performed on the first element of \(A\) and \(B\).

Analysis

- Coalesces global memory accesses

- Shared memory is used to reduce latency

- Only half the data loaded into shared memory is used; wasted memory bandwidth

Exercise

Hwu et al. suggest that you can first call the co-rank function to get the current and next output sections. This would increase memory bandwidth at the cost of an additional binary search.

- Where would this be done with respect to the tiled solution discussed in this section?

- How do these co-rank values differ from the ones used to calculate

C_currandC_next?

Hint: If we knew the co-rank value for the start of the next section, we could ensure that only the data below that index is loaded into shared memory.

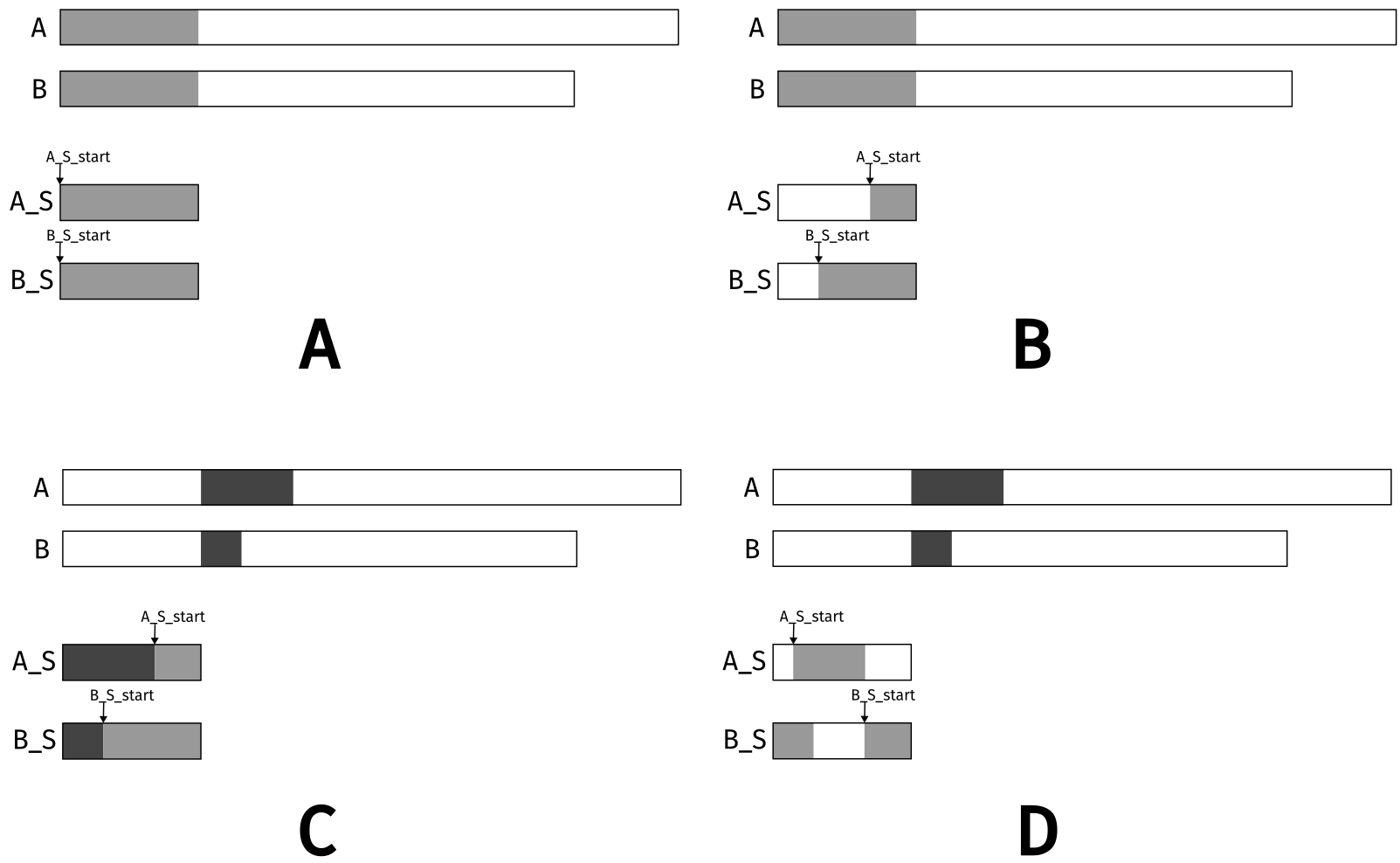

Circular Buffers

The tiled merge algorithm is a significant improvement over the basic merge kernel. One glaring issue is that only half of the data loaded into shared memory is used, leading to a waste of memory bandwidth. The circular buffer merge algorithm addresses this issue by using a circular buffer to store the input data. Instead of writing over the shared memory values on each iteration, the data to be used in the next iteration stays in shared memory. A portion of new data is loaded into shared memory based on how much was used in the previous iteration.

Figure 4: Circular buffer scheme (recreated from (Hwu, Kirk, and El Hajj 2022)).

The figure above outlines the main idea behind the circular buffer merge algorithm. Part A shows the initial data layout of global and shared memory. Only a portion of the data loaded into shared memory is used in the merge operation. This is shown in part B, where the blank portion of the shared memory depicts the data that was used. The light gray regions of shared memory are the left over data that can be used in the next iteration.

The next block of data is loaded into shared memory. Since some of the required data already exists from the last iteration, a smaller portion needs to be loaded. This is shown in part C, where the new data (dark gray) is loaded into shared memory. The starting indices for both arrays was already set in the previous iteration. Consecutive values are simple to calculate using the mod operator.

Part D shows the state of the arrays after the end of the second iteration. The blank areas in shared memory are the data that was used in the merge operation. For array A_S, the index wrapped around to the beginning of the array. It is ready to be used in the next iteration.

Implementation

A_consumed can be used to keep track of how many new elements need to be read into shared memory.

The co_rank and merge_sequential functions need to be updated to work with circular buffers. It is easier to treat the shared memory as an extended array, that way we avoid situations where the next index is less than the current index.

Co-Rank Function

int co_rank_circular(int k, int *A, int m, int *B, int n, int A_S_start, int B_S_start, int tile_length) {

int i = min(k, m);

int j = k - i;

int i_low = max(0, k-n);

int j_low = max(0, k-m);

int delta;

bool active = true;

while (active) {

int i_cir = (A_S_start + i) % tile_length;

int j_cir = (B_S_start + j) % tile_length;

int i_m_1_cir = (A_S_start + i - 1) % tile_length;

int j_m_1_cir = (B_S_start + j - 1) % tile_length;

if (i > 0 && j < n && A[i_m_1_cir] > B[j_cir]) {

delta = ((i - i_low + 1) >> 1);

j_low = j;

i -= delta;

j += delta;

} else if (j > 0 && i < m && B[j_m_1_cir] >= A[i_cir]) {

delta = ((j - j_low + 1) >> 1);

i_low = i;

j -= delta;

i += delta;

} else {

active = false;

}

}

return i;

}

In this updated version of the co-rank function, the user only needs to provide the start indices for the shared memory arrays along with the tile size.

Merge Sequential

void merge_sequential_circular(int *A, int m, int *B, int n, int *C, int A_S_start, int B_S_start, int tile_size) {

int i = 0;

int j = 0;

int k = 0;

while (i < m && j < n) {

int i_cir = (A_S_start + i) % tile_size;

int j_cir = (B_S_start + j) % tile_size;

if (A[i_cir] <= B[j_cir]) {

C[k] = A[i_cir];

i++;

} else {

C[k] = B[j_cir];

j++;

}

k++;

}

if (i == m) {

while (j < n) {

int j_cir = (B_S_start + j) % tile_size;

C[k] = B[j_cir];

j++;

k++;

}

} else {

while (i < m) {

int i_cir = (A_S_start + i) % tile_size;

C[k] = A[i_cir];

i++;

k++;

}

}

}

Again, this revision makes it easier on the user since they only need to provide the start indices for the shared memory arrays and the tile size. These are used to compute the indices for the circular buffer.

Circular Buffer Kernel

int c_curr = threadIdx.x * (tile_size / blockDim.x);

int c_next = (threadIdx.x + 1) * (tile_size / blockDim.x);

c_curr = (c_curr <= C_length - C_completed) ? c_curr : C_length - C_completed;

c_next = (c_next <= C_length - C_completed) ? c_next : C_length - C_completed;

int a_curr = co_rank_circular(c_curr,

A_s, min(tile_size, A_length - A_consumed),

B_s, min(tile_size, B_length - B_consumed),

A_curr, B_curr, tile_size);

int b_curr = c_curr - a_curr;

int a_next = co_rank_circular(c_curr,

A_s, min(tile_size, A_length - A_consumed),

B_s, min(tile_size, B_length - B_consumed),

A_curr, B_curr, tile_size);

int b_next = c_next - a_next;

merge_sequential_circular(A_s, a_next - a_curr, B_s, b_next - b_curr, &C[C_urr + C_completed + c_curr],

A_S_start + A_curr, B_S_start + B_curr, tile_size);

// Compute the indices that were used

counter++;

A_S_consumed = co_rank_circular(min(tile_size, C_length - C_completed),

A_s, min(tile_size, A_length - A_consumed),

B_s, min(tile_size, B_length - B_consumed),

A_S_start, B_S_start, tile_size);

B_S_consumed = min(tile_size, C_length - C_completed) - A_S_consumed;

A_consumed += A_S_consumed;

C_completed += min(tile_size, C_length - C_completed);

B_consumed = C_completed - A_consumed;

// Update the start indices for the next iteration

A_S_start = (A_S_start + A_S_consumed) % tile_size;

B_S_start = (B_S_start + B_S_consumed) % tile_size;

__syncthreads();

}

}

The first section of part 3 of the original kernel remains mostly unchanged, with the exceptions that the co-rank function and merge function are now called with the circular versions. The larger change is in the second half of the kernel. A_S_consumed and B_S_consumed are used to keep track of how much of the shared memory arrays were used. This is then used to offset the used indices from the original arrays. Finally, the start indices for the shared memory arrays are updated for the next iteration.

Thread Coarsening

The kernels presented in these notes already utilize thread coarsening. Each thread is responsible for a range of output values. The simple example presented earlier demonstrates what a non-coarse approach would look like. Each thread was only responsible for a single output value.