GPU Pattern: Parallel Histogram

These notes follow the presentation of the parallel histogram pattern in the book Programming Massively Parallel Processors: A Hands-on Approach (Hwu, Kirk, and El Hajj 2022).

Histograms

- Examples of histograms include:

- Frequency of words in a document

- Distribution of pixel intensities in an image

- Distribution of particle energies in a physics simulation

- Distribution of thread block execution times in a GPU kernel

Consider the program below which computes a histogram of the letters in a string. The input is assumed to be lower case. Since this is executed sequentially, there is no risk of multiple threads writing to the same memory location at the same time.

void histogram_sequential(char *data, unsigned int length, unsigned int *hist) {

for (unsigned int i = 0; i < length; i++) {

hist[data[i] - 'a']++;

}

}

To parallelize, we could launch a kernel which has each thread work with on character from the input. This presents a major problem when updating the histogram, as multiple threads may try and increment the same location simultaneously. This is called output interference.

Race Conditions

For example, thread 1 and thread 2 may have the letter ‘a’ as their input. They will both issue a read-modify-write procedure where the current value of the histogram is read, incremented, and then written back to memory. If thread 1 reads the value of the histogram before thread 2 writes to it, the value that thread 1 writes back will be incorrect. This is a classic example of a race condition. Depending on the timing, one thread could have read the updated value from the other thread, or both threads could have read the same value and incremented it, resulting in a loss of data.

Atomic Operations

One solution to this problem is to perform atomic operations. This is a special type of operation that locks a memory location while it is being updated. This prevents other threads from reading or writing to the same location until the operation is complete. Each thread attempting to access a memory location will be forced to wait until the lock is released.

The CUDA API provides several atomic operations:

atomicAddatomicSubatomicExchatomicMinatomicMaxatomicIncatomicDecatomicCAS

These are all intrinsic functions, meaning they are processed in a special way by the compiler. Instead of acting like a function call that comes with the typical overhead from the stack, these are implemented as inline machine instructions. The CUDA kernel below uses atomicAdd to increment the histogram.

__global__ void histogram_atomic(char *data, unsigned int length, unsigned int *hist) {

int i = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (i < length) {

atomicAdd(&hist[data[i] - 'a'], 1);

}

}

Latency of Atomic Operations

Atomic operations prevent the hardware from maximizing DRAM bursts since they serialize memory accesses. This can lead to a significant performance penalty. For each atomic operation, there are two delays: the delay from loading an element and the delay from storing the updated values.

Not all threads will be loading and storing to the same memory location; this is dependent on the number of bins used in the histogram. If the number of bins is small, the performance penalty will be greater. This analysis is further complicated based on the distribution of the data.

Atomic operations can be performed on the last level of cache. If the value is not in the cache, it will be brought into cache for future accesses. Although this does provide a performance benefit, it is not enough to offset the performance penalty of atomic operations.

Privatization

If much of the traffic is concentrated on a single area, the solution involves directing the traffic away in some manner. This is what privatization does. Since the bottleneck is the data load and store, privatization gives each thread its own private store so that it can update without contention. Of course, each copy must be combined in some way at the end. The cost of merging these copies is much less than the cost of the atomic operations. In practice, privatization is done for groups of threads, not individual ones.

The example above can be privatized by making a copy of the histogram for each thread block. The level of contention is much lower since only a single block will update their own private copy. All copies of the histogram are allocated as one monolithic array. Each individual block can use its local indices to offset the pointer. Private copies of values will likely still be cached in L2, so the cost of merging the copies is minimal.

For example, if we have 256 threads per block and 26 bins, we can allocate a \(26 \times 256\) array of integers. Each thread block will have its own copy of the histogram. The kernel below demonstrates this.

#define NUM_BINS 26

__global__ void histogram_privatized(char *data, unsigned int length, unsigned int *hist) {

int i = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (i < length) {

int pos = data[i] - 'a';

atomicAdd(&hist[blockIdx.x * NUM_BINS + pos], 1);

}

__syncthreads();

if (blockIdx.x > 0) {

for (unsigned int bin = threadIdx.x; bin < NUM_BINS; bin += blockDim.x) {

unsigned int binValue = hist[blockIdx.x * NUM_BINS + bin];

if (binValue > 0) {

atomicAdd(&hist[bin], binValue);

}

}

}

}

Each block is free to use its section of the histogram without contention. After all blocks have finished, the histogram is merged by summing the values of each bin across all blocks. This is done by having each block add its values to the global histogram. The __syncthreads function is used to ensure that all blocks have finished updating their private copies before the merge begins.

Each block after index 0 will add its values to the global histogram, represented by the first block. Only a single thread per block will be accessing each bin, so the only contention is with other blocks. If the bins are small enough, shared memory can be used to store the private copies. Even though an atomic operation is still required, the latency for loading and storing is reduced by an order of magnitude. The shared kernel below demonstrates this.

#define NUM_BINS 26

__global__ void histogram_privatized(char *data, unsigned int length, unsigned int *hist) {

__shared__ unsigned int hist_s[NUM_BINS];

for (unsigned int bin = threadIdx.x; bin < NUM_BINS; bin += blockDim.x) {

hist_s[bin] = 0;

}

__syncthreads();

int i = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (i < length) {

int pos = data[i] - 'a';

atomicAdd(&hist_s[pos], 1);

}

__syncthreads();

if (blockIdx.x > 0) {

for (unsigned int bin = threadIdx.x; bin < NUM_BINS; bin += blockDim.x) {

unsigned int binValue = hist_s[bin];

if (binValue > 0) {

atomicAdd(&hist[bin], binValue);

}

}

}

}

Coarsening

The bottleneck of using privatization moves from DRAM access to merging copies back to the public copy of the data. This scales up based on the number of blocks used, since each thread in a block will be sharing a bin in the worst case. If the problem exceeds the capacity of the hardware, the scheduler will serialize the blocks. If they are serialized anyway, then the cost of privatization is not worth it.

Coarsening will reduce the overhead of privatization by reducing the number of private copies that are committed to the public one. Each thread will process multiple elements.

Contiguous Partitioning

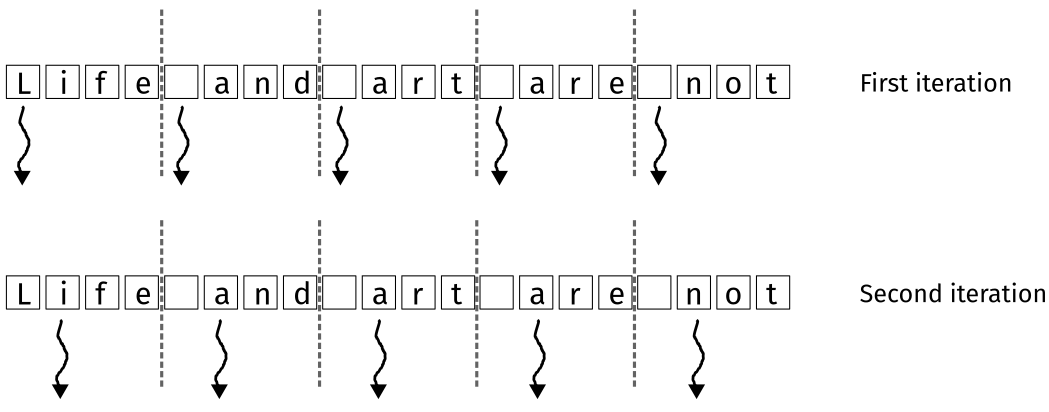

Figure 1: Contiguous partitioning. Recreated from (Hwu, Kirk, and El Hajj 2022).

Each thread is assigned a contiguous range of elements to process. The kernel is a straightforward extension of the privatized kernel. This approach works better on a CPU, where there are only a small number of threads. This is due to the caching behavior of the CPU. With so many threads on a GPU, it is less likely that the data will be in the cache since so many threads are competing.

#define NUM_BINS 26

__global__ void histogram_privatized_cc(char *data, unsigned int length, unsigned int *hist) {

__shared__ unsigned int hist_s[NUM_BINS];

for (unsigned int bin = threadIdx.x; bin < NUM_BINS; bin += blockDim.x) {

hist_s[bin] = 0;

}

__syncthreads();

int i = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (i < length) {

int pos = data[i] - 'a';

atomicAdd(&hist_s[pos], 1);

}

__syncthreads();

if (blockIdx.x > 0) {

for (unsigned int bin = threadIdx.x; bin < NUM_BINS; bin += blockDim.x) {

unsigned int binValue = hist_s[bin];

if (binValue > 0) {

atomicAdd(&hist[bin], binValue);

}

}

}

}

Interleaved Partitioning

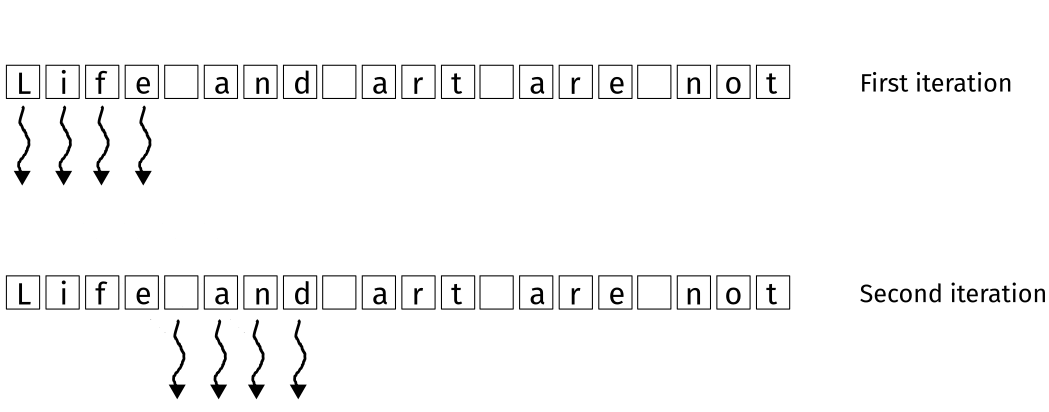

Figure 2: Interleaved partitioning. Recreated from (Hwu, Kirk, and El Hajj 2022).

Contiguous partitioning allowed for contiguous access to values relative to each thread. However, the memory was not contiguous with respect to other threads. In terms of DRAM accesses, each individual read from memory was too far apart to take advantage of coalescing. With interleaved partitioning, the memory can be accessed in a single DRAM access since the memory is coalesced.

#define NUM_BINS 26

__global__ void histogram_privatized_ic(char *data, unsigned int length, unsigned int *hist) {

__shared__ unsigned int hist_s[NUM_BINS];

for (unsigned int bin = threadIdx.x; bin < NUM_BINS; bin += blockDim.x) {

hist_s[bin] = 0;

}

__syncthreads();

int tid = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

for (int i = tid; i < length; i += blockDim.x * gridDim.x) {

int pos = data[i] - 'a';

if (pos >= 0 && pos < 26) {

atomicAdd(&hist_s[pos], 1);

}

}

__syncthreads();

if (blockIdx.x > 0) {

for (unsigned int bin = threadIdx.x; bin < NUM_BINS; bin += blockDim.x) {

unsigned int binValue = hist_s[bin];

if (binValue > 0) {

atomicAdd(&hist[bin], binValue);

}

}

}

}

In the code above, the main difference is the second for loop. The index i is incremented by blockDim.x * gridDim.x. This ensures that the threads of each block access memory in a contiguous manner rather than each thread being contiguous. The differences are visualized in the figures.

Aggregation

It is not uncommon that the input data will have a skewed distribution. There may be sections of the input that are locally dense. This will lead to a large number of atomic operations within a small area. To reduce the number of atomic operations, the input can be aggregated into a larger update before being committed to the global histogram. Consider the code below.

__global__ void histogram_aggregate(char *data, unsigned int length, unsigned int *histo) {

// Initialize shared memory

__shared__ unsigned int hist_s[NUM_BINS];

for (unsigned int bin = threadIdx.x; bin < NUM_BINS; bin += blockDim.x) {

hist_s[bin] = 0;

}

__syncthreads();

// Build histogram

unsigned int accumulator = 0;

int prevBinIdx = -1;

unsigned int tid = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

for (unsigned int i = tid; i a, length; i += blockDim.x * gridDim.x) {

int binIdx = data[i] - 'a';

if (binIdx == prevBinIdx) {

accumulator++;

} else {

if (prevBinIdx >= 0) {

atomicAdd(&hist_s[prevBinIdx], accumulator);

}

accumulator = 1;

prevBinIdx = binIdx;

}

}

if (accumulator > 0) {

atomicAdd(&hist_s[prevBinIdx], accumulator);

}

__syncthreads();

// Commit to global memory

for (unsigned int bin = threadIdx.x; bin < NUM_BINS; bin += blockDim.x) {

unsigned int binValue = hist_s[bin];

if (binValue > 0) {

atomicAdd(&histo[bin], binValue);

}

}

}

The difference in this kernel is the histogram loop in the middle. The previous bin index is tracked to determine if contiguous values would be aggregated. As long as the values are the same, the accumulator is increased. As soon as a new value is encountered, a batch update is performed. This reduces the number of atomic operations by a factor of the number of contiguous values.

If the data is relatively uniform, the cost of aggregation exceeds the simple kernel. If you are working with images, spatially local data will usually be aggregated. This kernel would be beneficial in that case. Another downside to the aggregated kernel is that it requires more registers and has an increased chance for control divergence. As with all implementations, you should profile this against your use case.

The Takeaway

Computing histograms is a common operation in fields such as image processing, natural language processing, and physics simulations. For example, a core preprocessing step for training a large language model is to compute the frequency of words in a corpus. This is a perfect example of a task that can be parallelized on a GPU.