GPU Pattern: Reduction

The following notes follow Chapter 10 of Programming Massively Parallel Processors (Hwu, Kirk, and El Hajj 2022).

Introduction

Given a set of values, a reduction produces a single output. It is an important part of many parallel algorithms including MapReduce. Other patterns that we have studied can also be viewed as reductions, such as GPU Pattern: Parallel Histogram. Implementing this parallel pattern requires careful consideration of thread communication, and will be the focus of these notes.

Many of the operations you rely on are examples of reductions. For example, the `sum` function is a reduction, as is the `max` function. A reduction can be viewed as a linear combination of the input values, or transformed values, and is often used to compute a summary statistic. If \(\phi(\cdot)\) is a binary operator, then a reduction computes the following:

\[ v = \phi(v, x_i)\ \text{for}\ i = 1, 2, \ldots, n, \]

where \(v\) is the accumulated value and \(x_i\) are the input values. The operator \(\phi(\cdot)\) can be any associative and commutative operation, such as addition or multiplication. Each operator has a corresponding identity element, such as 0 for addition or 1 for multiplication. The identity element is used to initialize the reduction and can be represented as \(v = v_0\) in the equation above.

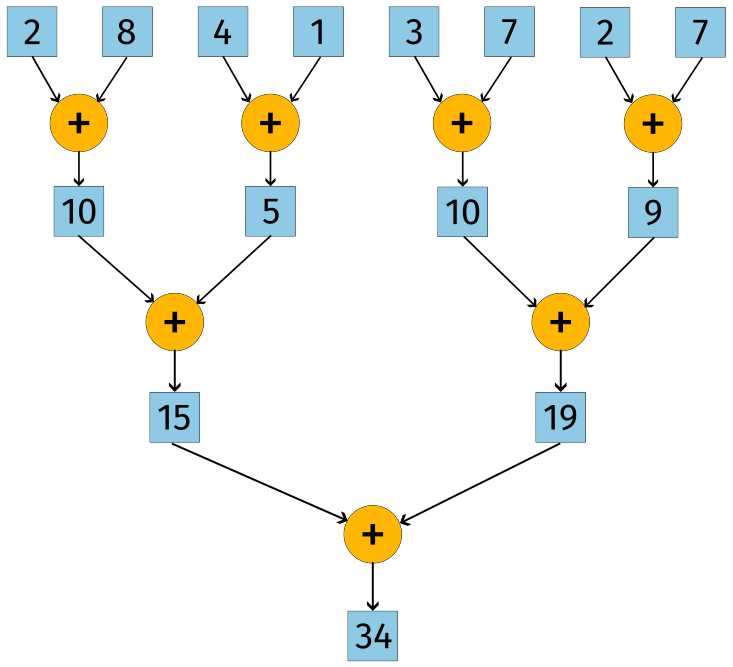

Reduction Trees

Reductions of any kind are well represented using trees. The first level of reduction maximizes the amount of parallelism. As the input is gradually reduced, fewer threads are needed.

In order to implement a parallel reduction, the chosen operator must be associative. For example, \(a + (b + c) = (a + b) + c\). The operator must also be commutative, such that \(a + b = b + a\).

Reduction trees reveal the logarithmic nature of parallel reductions. Just like divide and conquer algorithms, the number of threads is halved at each level of the tree. The number of levels in the tree is \(\log_2(n)\), where \(n\) is the number of input values. Given an input size of \(n = 1024\), the number of threads required is \(\log_2(1024) = 10\). This is a significant reduction from the original input size. The sequential version of this reduction would require 1023 operations.

A Simple Kernel

As mentioned above, reduction requires communication between threads. Since only the threads within a single block can communicate, we will focus on a block-level reduction. For now, each block can work with a total of 2048 input values based on the limitation of 1024 threads per block.

__global__ void sumReduceKernel(float *input, float *output) {

unsigned int i = 2 * threadIdx.x;

for (unsigned int stride = 1; stride <= blockDim.x; stride *= 2) {

// Only threads in even positions participate

if (threadIdx.x % stride == 0) {

input[i] += input[i + stride];

}

__syncthreads();

}

if (threadIdx.x == 0) {

*output = input[0];

}

}

Each thread is assigned to a single write location 2 * threadIdx.x. The stride is doubled after each iteration of the loop, effectively halving the number of active threads. The stride also determines the second value that is added to the first. By the last iteration, only one thread is active to perform that last reduction.

You can see that the kernel is simple, but it is also inefficient. There is a great deal of control divergence that will be addressed in the next section.

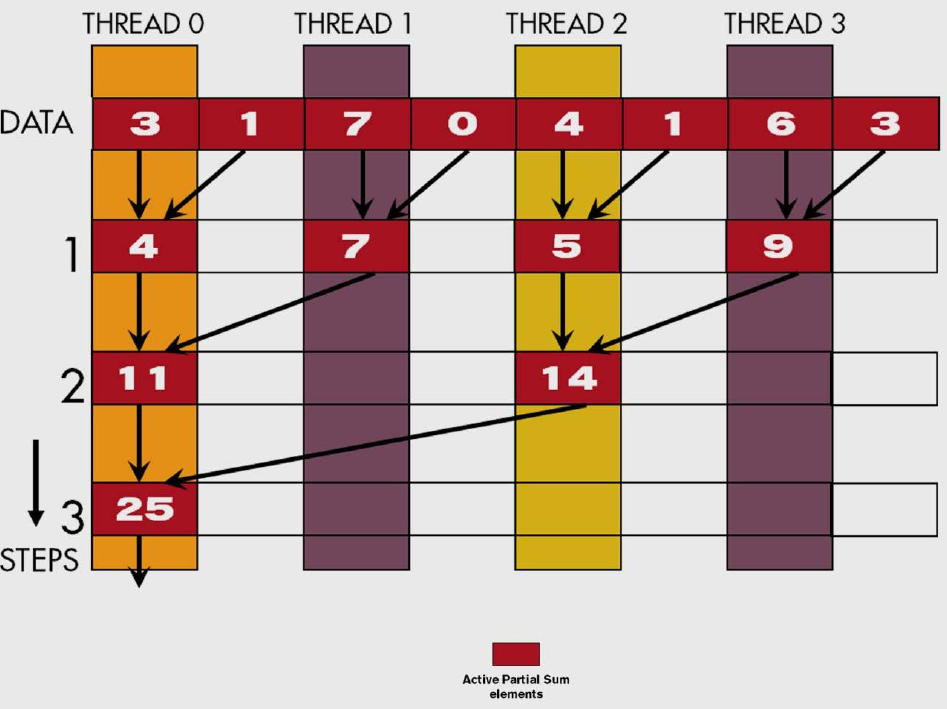

Minimizing Control Divergence

As we just saw, the key to optimizing a reduction kernel is to minimize control divergence and make sure as many threads stay active as possible. A warp of 32 threads would consume the execution resources even if half of them are inactive. As each stage of the reduction tree is completed, the amount of wasted resources increases. Depending on the input size, entire warps could be launched and then immediately become inactive.

The number of execution resources consumed is proportional to the number of active warps across all iterations. We can compute the number of resources consumed as follows:

\[ (\frac{5N}{64} + \frac{N}{128} + \frac{N}{256} + \cdots + 1) * 32 \]

where \(N\) is the number of input values. Each thread operates on 2 values, so \(\frac{N}{2}\) are launched in total. Since every warp has 32 threads, a total of \(\frac{N}{64}\) warps are launched. For the first 5 iterations, all warps will be active. The 5th iteration only has 1 active thread in each warp. On the 6th iteration, the number of active warps is halved, and so on.

For an input of size \(N = 1024\), the number of resources consumed is \((80 + 8 + 4 + 2 + 1) * 32 = 3040\). The total number of results committed by the active threads is equal to the number of operations performed, which is \(N - 1 = 1023\). The efficiency of the kernel is then \(\frac{1023}{3040} = 0.34\). Only around 34% of the resources are used to perform the reduction.

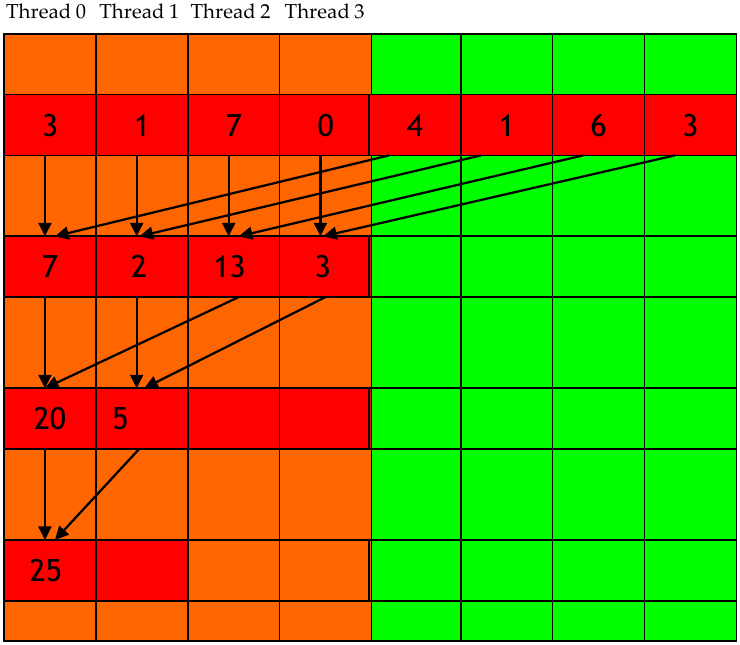

Rearranging the Threads

A simple rearrangement of where the active results are stored can improve the efficiency of the kernel by reducing control divergence. The idea is to keep the threads that own the results of the reduction close together. Instead of increasing the stride, it should be decreased. The figure below shows the rearrangement of the threads.

__global__ void sumReduceKernel(float *input, float *output) {

unsigned int i = threadIdx.x;

for (unsigned int stride = blockDim.x; stride >= 1; stride /= 2) {

if (i < stride) {

input[i] += input[i + stride];

}

__syncthreads();

}

if (threadIdx.x == 0) {

*output = input[0];

}

}

The kernel itself is effectively the same, but the rearrangement of the threads ensures that each warp has less control divergence. Additionally, warps that drop off after each iteration are no longer consuming execution resources. For an input of 256, the first 4 warps are fully utilized (barring the last thread of the last warp). After the first iteration, the number of active warps is halved. Warps 3 and 4 are now fully inactive, leaving warps 1 and 2 to perform the reduction operation on all threads. We can compute the number of resources consumed under this new arrangement as follows:

\[ (\frac{N}{64} + \frac{N}{128} + \frac{N}{256} + \cdots + 1 + 5) * 32 \]

At each iteration, half of warps become inactive and no longer consume resources. The last warp will consume execution resources for all 32 threads, even though the number of active threads is less than 32. For our input of size \(N = 1024\), the number of resources consumed is \((16 + 8 + 4 + 2 + 1 + 5) * 32 = 1152\), resulting in an efficiency of \(\frac{1023}{1152} = 0.89\). This is a significant improvement over the original kernel. This will increase based on the input size.

Memory Divergence of Reduction

Does this kernel take advantage of memory coalescing? Each thread reads and writes from and to its assigned location. It also makes a read from a location that is a stride away. These locations are certainly not adjacent and will not be coalesced.

Adjacent threads do not access adjacent locations. The warp itself is unable to coalesce the thread requests into a single global memory request. Each data element is 4 bytes. Since each of the 32 threads in a warp are accessing their assigned locations with a separation of stride, the 64 * 4 bytes will require two 128 byte memory requests to access the data. With each iteration, the assigned locations will always be separated such that two 128 byte memory requests will need to be made. Only on the last iteration, where only a single thread accesses a single assigned location, will a single memory request be made.

The convergent kernel from the last section takes advantage of memory coalescing, leading to fewer memory requests.

Reducing the number of global memory requests

As we saw with tiling in GPU Performance Basics, we can reduce the number of global memory requests by using shared memory. Threads write their results to global memory, which is read again in the next iteration. By keeping the intermediate results in shared memory, we can reduce the number of global memory requests. If implemented correctly, only the original input values will need to be read from global memory.

__global__ void sumReduceSharedKernel(float *input, float *output) {

__shared__ float input_s[BLOCK_DIM];

unsigned int i = threadIdx.x;

input_s[i] = input[i] + input[i + BLOCK_DIM];

for (unsigned int stride = blockDim.x / 2; stride >= 1; stride /= 2) {

__syncthreads();

if (i < stride) {

input_s[i] += input_s[i + stride];

}

}

if (i == 0) {

*output = input_s[0];

}

}

At the very top of this kernel, the necessary input is loaded from global memory, added, and written to shared memory. This is the only time global memory is accessed, with the exception of the final write to the output. The call to syncthreads() moves to the top so that the shared memory is guaranteed before the next update.

This approach not only requires fewer global memory requests, but the original input is left unmodified.

Hierarchical Reduction

One major assumption that has been made in each of these kernels is that they are running on a single block. Thread synchronization is critical to the success of the reduction. If we want to reduce a larger number of input across multiple blocks, the kernel should allow for independent execution. This is achieved by segmenting the input and performing a reduction on each segment. The final reduction is then performed on the results of the segment reductions.

__global__ void sumReduceHierarchicalKernel(float *input, float *output) {

__shared__ float input_s[BLOCK_DIM];

unsigned int segment = 2 * blockDim.x * blockIdx.x;

unsigned int i = segment + threadIdx.x;

unsigned int t = threadIdx.x;

input_s[t] = input[i] + input[i + BLOCK_DIM];

for (unsigned int stride = blockDim.x / 2; stride >= 1; stride /= 2) {

__syncthreads();

if (t < stride) {

input_s[t] += input_s[t + stride];

}

}

if (t == 0) {

atomicAdd(output, input_s[0]);

}

}

Each block has its own shared memory and can independently perform the reduction. Depending on the completion order, an atomic operation to add the local result is necessary.

Thread Coarsening - Back Again

Thread coarsening was first analyzed in the context of matrix multiplication in GPU Performance Basics. Whenever the device does not have enough resources to execute the number of threads requested, it is forced to serialize the execution. In this case, we can serialize the work done by each thread so that no extra overhead is incurred. Another benefit to thread coarsening is improved data locality.

Successive iterations increase the amount of inactive warps. For reduction, thread coarsening can be applied by increasing the number of elements that each one processes. If the time to perform the arithmetic is much faster than the time to load the data, then thread coarsening can be beneficial. We could further analyze our program to determine the optimal coarsening factor.

__global__ coarsenedSumReductionKernel(float *input, float *output) {

__shared__ float input_s[BLOCK_DIM];

uint segment = COARSE_FACTOR * 2 * blockDim.x * blockIdx.x;

uint i = segment + threadIdx.x;

uint t = threadIdx.x;

float sum = input[i];

for (uint tile = 1; tile < COARSE_FACTOR * 2; tile++) {

sum += input[i + tile * BLOCK_DIM];

}

input_s[t] = sum;

for (uint stride = blockDim.x / 2; stride >= 1; stride /= 2) {

__syncthreads();

if (t < stride) {

input_s[t] += input_s[t + stride];

}

}

if (t == 0) {

atomicAdd(output, input_s[0]);

}

}

In the coarsened version, less thread communication is required since the first several steps are computed in a single thread.