GPU Pattern: Stencils

Differential Equations

Any computational problem requires discretization of data or equations so that they can be solved numerically. This is fundamental in numerical analysis, where differential equations need to be approximated.

Structured grids are used in finite-difference methods for solving partial differential equations (PDEs). Approximate derivatives can be computed point-wise by considering the neighbors on the grid. As we saw earlier in this course, a grid representation is a natural way to think about data parallelism.

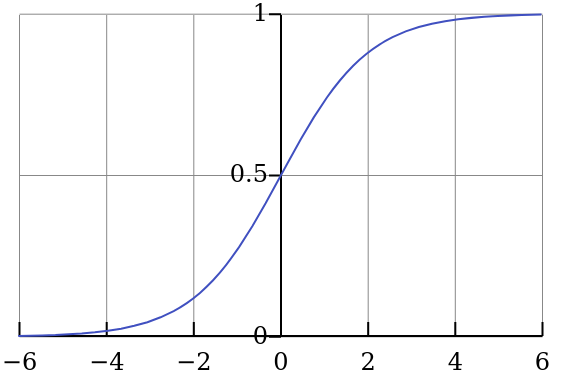

Depending on the function and level of discretization, interpolation will be more or less accurate. Consider the logistic sigmoid function sampled at 4 points. In the middle, linear interpolation would work just fine. Near the bends of the function, a linear approximation would introduce error. The closer the spacing, the more accurate a linear approximation becomes. The downside is that more memory is required to store the points.

The precision of the data type also plays an important role. Higher precision data types like double require more bandwidth to transfer and will typically require more cycles when computing arithmetic operations.

Stencils

A stencil is a geometric pattern of weights applied at each point of a structured grid. The points on the grid will derive their values from neighboring points using some numerical approximation. For example, this is used to solve differential equations. Consider a 1D grid of discretized values from a function \(f(x)\). The finite difference approximation can be used to find \(f’(x)\):

\[ f’(x) = \frac{f(x+h) - f(x-h)}{2h} + O(h^2) \]

In code, this would look like:

__global__ void finite_difference(float *f, float *df, float h) {

int i = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

df[i] = (f[i+1] - f[i-1]) / (2 * h);

}

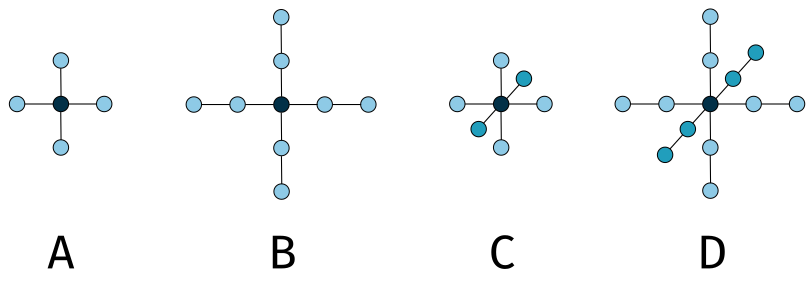

A PDE of two variables can be solved using a 2D stencil. Likewise, a PDE of three variables can be solved using a 3D stencil. The figures below show examples of common 2D and 3D stencils. Note that they typically have an odd number of points so that there is a center point.

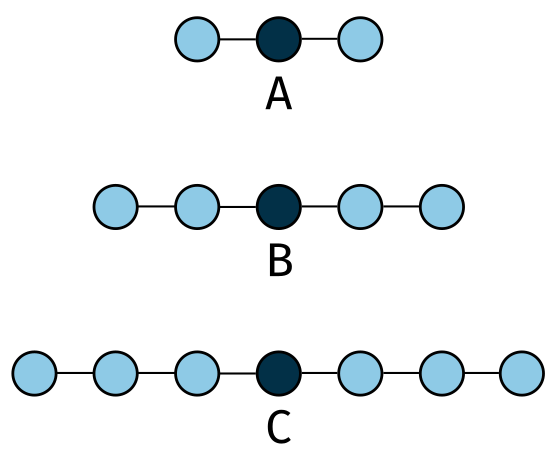

Figure 2: 1D stencils. Recreated from (Hwu, Kirk, and El Hajj 2022).

The 1D stencils shown above are used to approximate the first-order (A), second-order (B), and third-order (C) derivatives of a function \(f(x)\).

Figure 3: 2D and 3D stencils. Recreated from (Hwu, Kirk, and El Hajj 2022).

The 2D stencils shown above are used to approximate first-order (A) and second-order (B) derivatives of a function \(f(x, )\). Likewise, the 3D stencils are used to approximate first-order (C) and second-order (D) derivatives of a function \(f(x, y, z)\).

A stencil sweep is the process of applying the stencil to all points on the grid, similar to how a convolution is applied. There are many similarities between the two, but the subtle differences will require us to think differently about how to optimize them.

Example: Basic Stencil

The code below presents a naive kernel for a stencil pattern using a 3D seven-point stencil.

__global__ void stencil_kernel(float *in, float *out, unsigned int N) {

unsigned int i = blockIdx.z * blockDim.z + threadIdx.z;

unsigned int j = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y;

unsigned int k = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (i >= 1 && i < N - 1 && j >= 1 && j < N - 1 && k >= 1 && k < N - 1) {

out[i*N*N + j*N + k] = c0 * in[i*N*N + j*N + k]

+ c1 * in[i*N*N + j*N + (k - 1)]

+ c2 * in[i*N*N + j*N + (k + 1)]

+ c3 * in[i*N*N + (j - 1)*N + k]

+ c4 * in[i*N*N + (j + 1)*N + k]

+ c5 * in[(i - 1)*N*N + j*N + k]

+ c6 * in[(i + 1)*N*N + j*N + k];

}

}

This example assumes the input and output are 3D grids. For this particular stencil, you should try to identify the number of memory accesses and operations performed. Can you already see some opportunities for optimization?

Tiled Stencil

Just like with convolution, it is possible to use shared memory to improve the performance of a stencil. The code below shows a tiled stencil kernel that uses shared memory.

__global__ void stencil_kernel(float *in, float *out, unsigned int N) {

__shared__ float tile[IN_TILE_DIM][IN_TILE_DIM][IN_TILE_DIM];

int i = blockIdx.z * OUT_TILE_DIM + threadIdx.z - 1;

int j = blockIdx.y * OUT_TILE_DIM + threadIdx.y - 1;

int k = blockIdx.x * OUT_TILE_DIM + threadIdx.x - 1;

if (i >= 0 && i < N && j >= 0 && j < N && k >= 0 && k < N) {

tile[threadIdx.z][threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x] = in[i*N*N + j*N + k];

}

__syncthreads();

if (i >=1 && i < N-1 && j >= 1 && j < N-1 && k >= 1 && k < N-1) {

if (threadIdx.z >= 1 && threadIdx.z < IN_TILE_DIM-1 &&

threadIdx.y >= 1 && threadIdx.y < IN_TILE_DIM-1 &&

threadIdx.x >= 1 && threadIdx.x < IN_TILE_DIM-1) {

out[i*N*N + j*N + k] = c0 * tile[threadIdx.z][threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x]

+ c1 * tile[threadIdx.z][threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x - 1]

+ c2 * tile[threadIdx.z][threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x + 1]

+ c3 * tile[threadIdx.z][threadIdx.y - 1][threadIdx.x]

+ c4 * tile[threadIdx.z][threadIdx.y + 1][threadIdx.x]

+ c5 * tile[threadIdx.z - 1][threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x]

+ c6 * tile[threadIdx.z + 1][threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x];

}

}

}

Just like before, the threads of a block will first collaborate to load a tile with the relevant data. Stencil patterns are more sparse than convolutional filters and require less data to be loaded into shared memory. This will be the central detail in our analysis of stencil patterns.

Scaling stencil size vs. Convolution filter size

Convolutions are more efficient as the size increases since more values are accessed in shared memory. For a \(3 \times 3\) convolution, the upper bound on compute to memory ratio is 4.5 OP/B. A 5 point 2D stencil has a ratio of 2.5 OP/B due to the sparsity of the pattern. The threads in the block would load the diagonal values from global memory, but each thread would only use the 5 points defined by the kernel.

Tiling Analysis

Let us consider the effectiveness of shared memory tiling where each thread performs 13 floating-point ops (7 multiplies and 6 adds) with each block using \((T - 2)^3\) threads. Each block also performs \(T^3\) loads of 4 bytes each. The compute to memory ratio can be express as:

\[ \frac{13(T - 2)^3}{4T^3} = \frac{13}{4} \left(1 - \frac{2}{T}\right)^3 \]

Due to the low limit on threads, the size of \(T\) is typically small. This means there is a smaller amount of reuse of data in shared memory. The ratio of floating-point ops to memory accesses will be low.

Each warp loads values from 4 distant locations in global memory. This means that the memory accesses are not coalesced: the memory bandwidth is low. Consider an \(8 \times 8 \times 8\) block. A warp of 32 threads will load 4 rows of 8 values each. The values within each row contiguous, but the rows are not contiguous.

Thread Coarsening

Stencils do not benefit from shared memory as much as convolutions due to the sparsity of the sampled points. Most applications of the stencil patterns work with a 3D grid, resulting in relatively small tile sizes per block.

A solution to this is to increase the amount of work each thread performs, AKA thread coarsening. The price paid for parallelism in the stencil pattern is the low frequency of memory reuse.

Each thread performs more work in the \(z\) direction for a 3D seven-point stencil. All threads collaborate to load in a \(z\) layer at time from \(z-1\) to \(z+1\). There are then 3 different shared memory tiles per block. After computing values in the current output tile, the shared memory is rearranged for the next layer. This means that there are more transfers between shared memory as opposed to global memory.

The threads are launched to work with a 2D tile at a time, so the size of the block is now \(T^2\). This means we can use a larger value for \(T\). The compute to memory ratio is almost doubled under this scheme. Additionally, the amount of shared memory required is \(3T^2\) rather than \(T^3\).

__global__ void stencil_kernel(float *in, float *out, unsigned int N) {

int iStart = blockIdx.z * OUT_TILE_DIM;

int j = blockIdx.y * OUT_TILE_DIM + threadIdx.y - 1;

int k = blockIdx.x * OUT_TILE_DIM + threadIdx.x - 1;

__shared__ float inPrev_s[IN_TILE_DIM][IN_TILE_DIM];

__shared__ float inCurr_s[IN_TILE_DIM][IN_TILE_DIM];

__shared__ float inNext_s[IN_TILE_DIM][IN_TILE_DIM];

if (iStart - 1 >= 0 && iStart - 1 < N && j >= 0 && j < N && k >= 0 && k < N) {

inPrev_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x] = in[(iStart - 1)*N*N + j*N + k];

}

if (iStart >= 0 && iStart < N && j >= 0 && j < N && k >= 0 && k < N) {

inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x] = in[iStart*N*N + j*N + k];

}

for (int i = iStart; i < iStart + OUT_TILE_DIM; i++) {

if (i + 1 >= 0 && i + 1 < N && j >= 0 && j < N && k >= 0 && k < N) {

inNext_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x] = in[(i + 1)*N*N + j*N + k];

}

__syncthreads();

if (i >= 1 && i < N - 1 && j >= 1 && j < N - 1 && k >= 1 && k < N - 1) {

if (threadIdx.y >= 1 && threadIdx.y < IN_TILE_DIM - 1 &&

threadIdx.x >= 1 && threadIdx.x < IN_TILE_DIM - 1) {

out[i*N*N + j*N + k] = c0 * inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x]

+ c1 * inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x - 1]

+ c2 * inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x + 1]

+ c3 * inCurr_s[threadIdx.y - 1][threadIdx.x]

+ c4 * inCurr_s[threadIdx.y + 1][threadIdx.x]

+ c5 * inPrev_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x]

+ c6 * inNext_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x];

}

}

__syncthreads();

inPrev_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x] = inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x];

inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x] = inNext_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x];

}

}

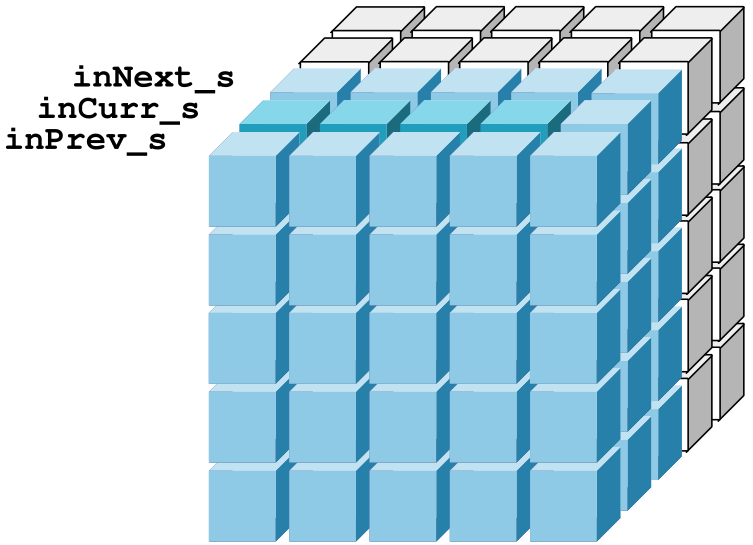

This kernel is visualized below with a block size of \(6 \times 6\). The left and top sides of the tile have been removed for clarity. All of the blue blocks are loaded from global memory. The dark blue blocks represent the active plane that is used to compute the corresponding output values. After the current plane is completed, the block synchronizes before moving the current values to the previous plane and loads the next plane’s values into the current plane inCurr_s.

Register Tiling

In the coarsening solution presented above, each thread works with a single element in the previous and next shared memory tiles. There are 4 elements in that example that really need to be loaded from shared memory. For the 3 elements that are only required by the current thread, they can be loaded into registers.

Since only the values in the \(x-y\) direction are required for shared memory, the amount of memory used is reduced by \(\frac{1}{3}\).

__global__ void stencil_kernel(float *in, float *out, unsigned int N) {

int iStart = blockIdx.z * OUT_TILE_DIM;

int j = blockIdx.y * OUT_TILE_DIM + threadIdx.y - 1;

int k = blockIdx.x * OUT_TILE_DIM + threadIdx.x - 1;

float inPrev;

float inCurr;

float inNext;

__shared__ float inCurr_s[IN_TILE_DIM][IN_TILE_DIM];

if (iStart - 1 >= 0 && iStart - 1 < N && j >= 0 && j < N && k >= 0 && k < N) {

inPrev = in[(iStart - 1)*N*N + j*N + k];

}

if (iStart >= 0 && iStart < N && j >= 0 && j < N && k >= 0 && k < N) {

inCurr = in[iStart*N*N + j*N + k];

inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x] = inCurr;

}

for (int i = iStart; i < iStart + OUT_TILE_DIM; i++) {

if (i + 1 >= 0 && i + 1 < N && j >= 0 && j < N && k >= 0 && k < N) {

inNext = in[(i + 1)*N*N + j*N + k];

}

__syncthreads();

if (i >= 1 && i < N - 1 && j >= 1 && j < N - 1 && k >= 1 && k < N - 1) {

if (threadIdx.y >= 1 && threadIdx.y < IN_TILE_DIM - 1 &&

threadIdx.x >= 1 && threadIdx.x < IN_TILE_DIM - 1) {

out[i*N*N + j*N + k] = c0 * inCurr

+ c1 * inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x - 1]

+ c2 * inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x + 1]

+ c3 * inCurr_s[threadIdx.y - 1][threadIdx.x]

+ c4 * inCurr_s[threadIdx.y + 1][threadIdx.x]

+ c5 * inPrev

+ c6 * inNext;

}

}

__syncthreads();

inPrev = inCurr;

inCurr = inNext;

inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x] = inNext_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x];

}

}

The kernel always has the active plane in shared memory. Every thread collectively store the previous and next planes in registers.

The larger the stencil size, the more registers are required per thread. In this case, a tradeoff between shared memory space and register usage could be made. This will be explored in your lab.

Summary

Stencils are a useful pattern for solving differential equations. They have some similarities to convolutions, but present unique challenges in terms of optimization. The sparsity of the pattern means that shared memory is not as effective as it is for convolutions. Thread coarsening and register tiling are two techniques that can be used to improve performance.

Questions

- How many registers per thread are required for a 3D seven-point stencil, 3D nine-point stencil, and 3D 27-point stencil?

- How do convolutions relate to stencil patterns? Could you implement a stencil pattern using a convolution filter?

- When implementing any stencil, how much does the kernel benefit from loading values on the same row from shared memory? If they weren’t in shared memory, would they be more likely to be read together in a DRAM burst? Try to verify this in the profiler.