Image Segmentation

Resources

- https://www2.eecs.berkeley.edu/Research/Projects/CS/vision/bsds/ (Berkeley Segmentation Database)

- https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.15203v2 (SegFormer)

- https://arxiv.org/abs/1703.06870 (Mask R-CNN)

- https://github.com/sithu31296/semantic-segmentation (Collection of SOTA models)

Introduction

Feature extraction methods such as SIFT provide us with many distinct, low-level features that are useful for providing local descriptions images. We now “zoom out” and take a slightly higher level look at the next stage of image summarization. Our goal here is to take these low-level features and group, or fit, them together such that they represent a higher level feature. For example, from small patches representing color changes or edges, we may wish to build higher-level feature representing an eye, mouth, and nose.

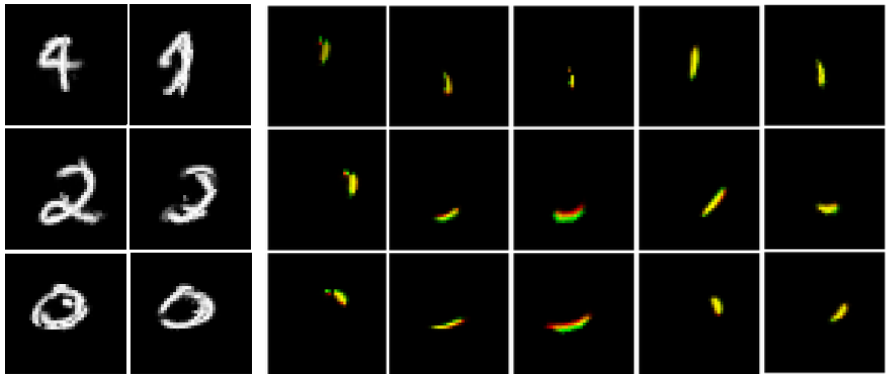

Figure 1: Capsule networks learn template components that make up handwritten images (Kosiorek et al.)

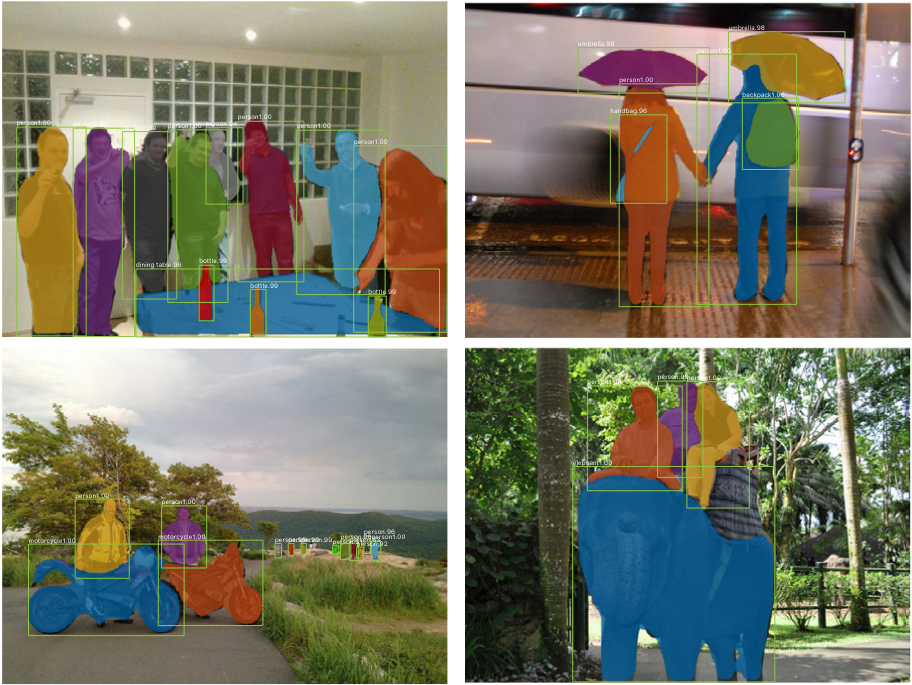

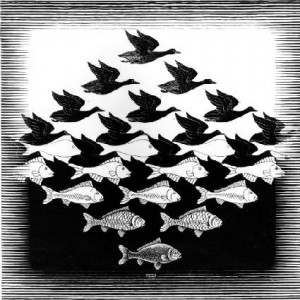

The goal of image segmentation is to obtain a compact representation of distinct features in an image. We will see that this task is loosely defined and will vary from application to application. For example, in one task we may wish to segment individual people detected in an image. In another task, we may wish to segment the clothes they are wearing to identify certain fashion trends or make predictions about the time of year based on an image.

Image segmentation is one of the oldest tasks in computer vision and, as such, encompasses many methods and techniques. The following list of segmentation categories is not exhaustive, but covers many notable approaches.

- Region: Methods that group by regions and either grow, merge, or spread them fall into this category. A simple region-based approach would be to apply morphological operations on thresholded images.

- Boundary: Separating parts of the image based on edges, lines, or specific points.

- Clustering: Methods that utilize some form of clustering such as K-means or Gaussian models to group pixels fall into this category.

- Watershed: Groups pixels by treating the image as a topographical map. Consider a large pool with 4 local minima such that there are 4 tiny pools inside it. As you fill the entire pool up, eventually the water line from each of the 4 smaller pools will touch, creating a boundary between different regions.

- Graph-Based: Segmentation algorithms based on graph theory.

- Mean-Shift: Clustering methods fall into this category.

- Normalized Cuts: Quantifies the strength of connectedness between groups before separating weak connections.

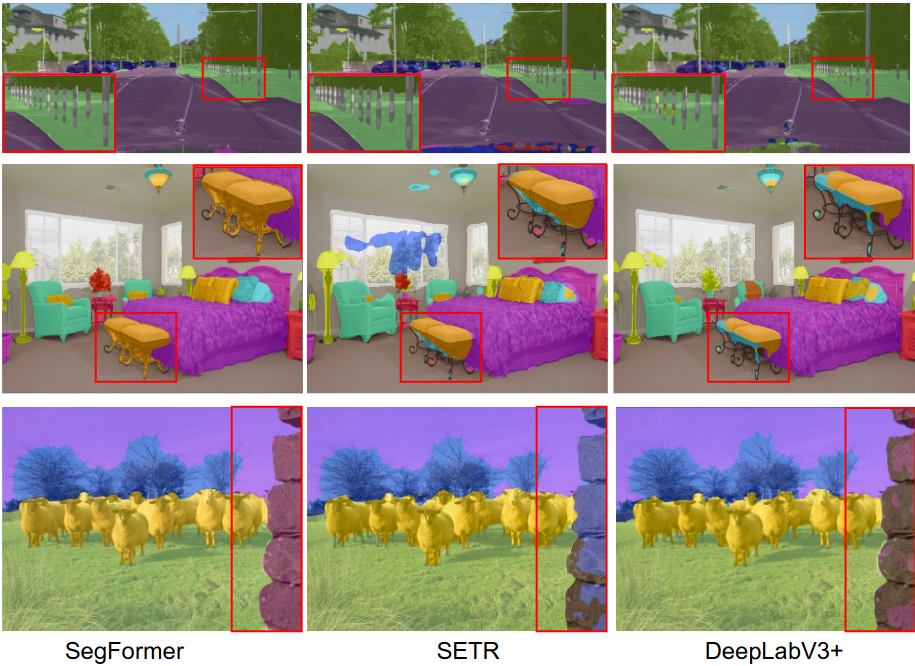

Each of these styles can be used for general segmentation or a well-defined downstream task. General segmentation may be used for unsupservised segmentation of an image for the purpose of creating superpixels (Achanta et al. 2012). A common downstream task is semantic segmentation, where distinct objects in an image are segmented. An even more difficult version of semantic segmentation is instance segmentation where multiple instances of objects are labelled separately.

Gestalt Theory

Gestalt psychology provides a theory of perception emphasizing grouping patterns. Examining different ways to think about grouping sheds light on the open-endedness of segmentation in general.

Grouping

At the pixel-level, features such as edges will look similar regardless of the context. An edge segment from a car will look similar to that of a building at a small enough scale. As soon as those features are grouped together, their representation completely changes. A collection of edges becomes a square or a corner. The higher-level of grouping we have, the more that the collection of features begin to diverge from each other.

ConvNet Gradient Visualization

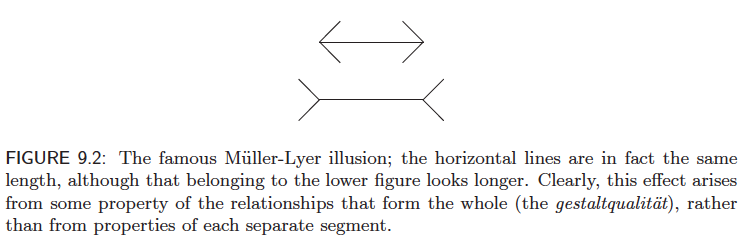

Consider the famouse Muller-Lyer illusion seen below.

Looking at the details individually, it is easier to see that the lines are the same length. When considering the grouped features around them, they appear different.

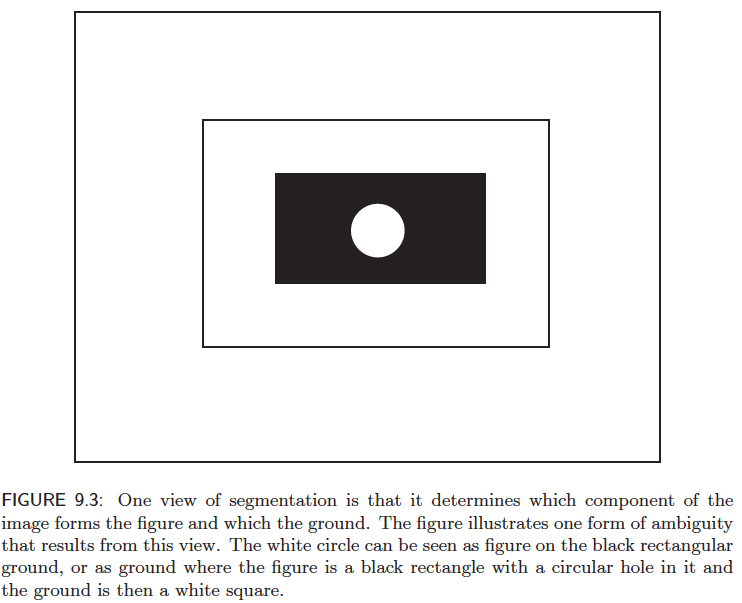

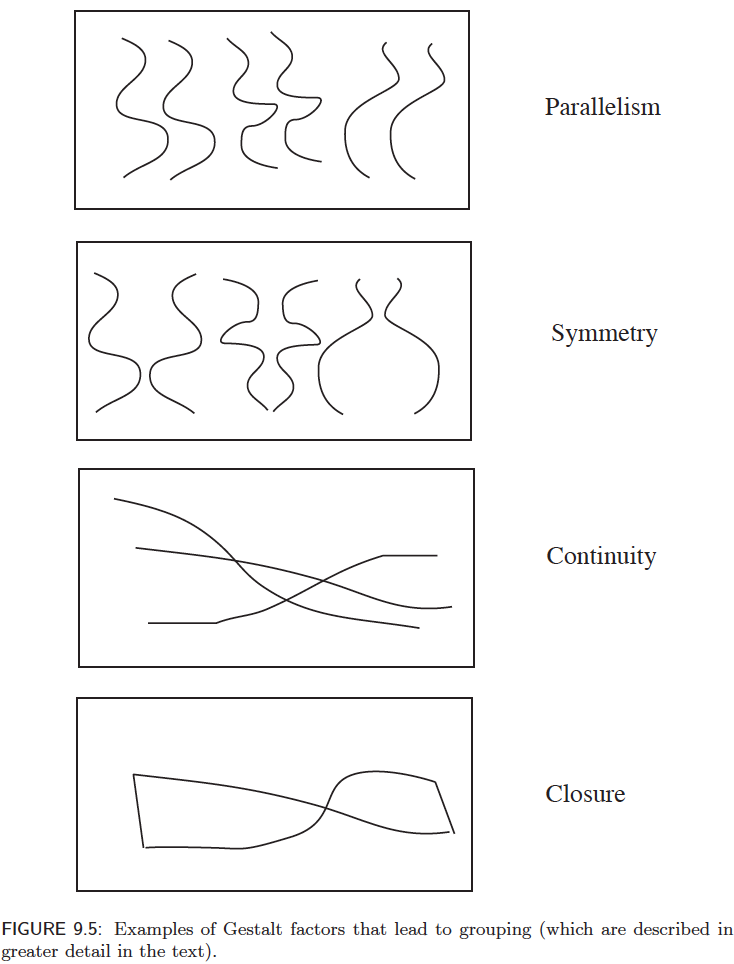

Another view of segmentation considers what is the figure versus what is the ground, or background.

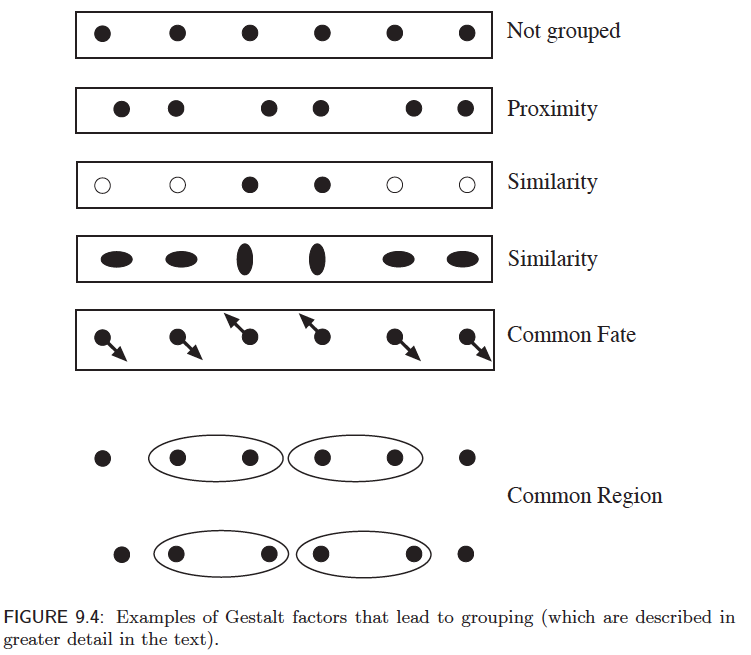

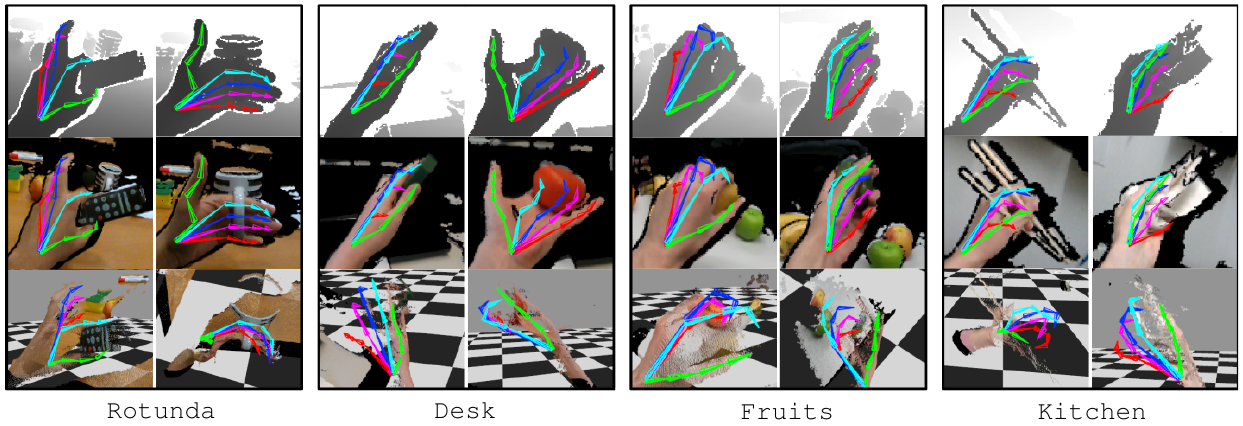

The Gestalt school of psychology posited that grouping was the key to visual understanding. Towards establishing a theory of segmentation, a set of factors was proposed:

- Proximity - Group elements that are close together.

- Similarity - Elements that share some sort of measurable similarity are grouped.

- Common fate - Often tied to temporal features, elements with a similar trajectory are grouped.

- Common region - Elements enclosed in a region are part of the same group. This region could be arbitrary.

- Parallelism - Parallel elements are grouped.

- Closure - Lined or curves that are closed.

- Symmetry - Elements exhibiting some sort of symmetry. For example, a mirrored shaped.

- Continuity - Continuous curves are grouped.

- Familiar configuration - Lower level elements, when grouped together, form a higher level object.

Intuiting applications for some of these rules is easier than others. For example, familiar configuration suggests that some familiar object can be identified by the sum of its parts. This is especially helpful for problems where the whole object is occluded.

Common fate is a useful rule when considering tracking an object or group of objects over a series of frames. Even something a simple as frame differencing is an efficient preprocessing step to removing unrelated information.