Introduction to Python

These notes are focused on introducing programming with Python for those without a technical background.

Introduction

The official website provides the following description of Python.

Python is an interpreted, interactive, object-oriented programming language. It incorporates modules, exceptions, dynamic typing, very high level dynamic data types, and classes. It supports multiple programming paradigms beyond object-oriented programming, such as procedural and functional programming. Python combines remarkable power with very clear syntax. It has interfaces to many system calls and libraries, as well as to various window systems, and is extensible in C or C++. It is also usable as an extension language for applications that need a programmable interface. Finally, Python is portable: it runs on many Unix variants including Linux and macOS, and on Windows.

If you have never studied any programming languages before, much of this description will be useless to you. There is no context for the types of programming (object-oriented, functional, etc.), and the fact that is extensible in C or C++ may mean absolutely nothing.

Why Python?

Given that this course is for prospective data science practitioners, and the fact that we have less than a month to cover a programming language, Python is a natural choice. It is widely used in the field of Machine Learning and is gaining more and more ground over R (or so I think) for statistics. There are many third-party libraries for data analysis, visualization, and just about any other data science application we can think of.

How to use these notes

These notes are organized to follow each major topic in Python. They will also follow the free online book Python for Everybody. These particular lecture notes will start with Chapter 2: Variables, expressions, and statements. It is highly recommended that you run the examples on your own machine, and you are encouraged to make changes. Try to break the code and fix it again. Have it output something different and change the program’s purpose entirely.

A Python notebook will accompany each lecture and will be accessible on my GitHub page. I will also include code snippets directly in this article to highlight a particular example or point.

Programming is Hard

Before we dive into the language itself, there are a few things that are important to keep in mind. First, programming is hard. It is a skill that requires practice. The tools that you use to program are constantly evolving to keep up with the use-cases of the day. A processor is a complex calculator which means we have to be extremely explicit about the instructions we provide. If you are picking this up for the first time, remember to be patient and be kind to yourself. You will be able to work on big projects that are important to you, but we all have to start somewhere.

Resources are Finite

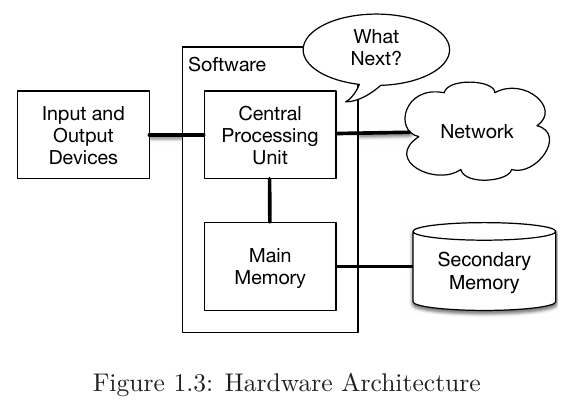

Another important thing to remember is that we are working with limited resources. There is only so much memory and storage space that we can access. These notes are not meant to accompany a full course on hardware architectures, so we will use the following diagram to visualize this point.

The closer the memory is to the CPU, the quicker it can be accessed. Most of the algorithms and data structures we will study in this course will be used with data in main memory. The trade off is that memory that is closer to the CPU is more expensive and has reduced capacity when compared with secondary memory. When we start working with larger sources of data, we will need to adapt our solutions to work with memory that is not directly accessible through a local machine. For now, keep this picture in mind as we dive into Python.

Programming with Python

Programming languages provide the following features:

- a way to write instructions (syntax, statements, expressions)

- a way to execute a complex series of instructions (functions)

- a way to store the results of computations and represent data (variables, data structures)

They mostly differ in how the language is written, the syntax. Consider the following snippet of Python code:

username = "test"

password = "securePass1"

user_logged_in = False

if login(username, password) == True:

user_logged_in = True

Even if you have never seen any Python code before, you could probably figure out what this block of code is doing. First, 3 variables are defined which store the username, password, and a flag that represents whether or not the user is logged into the system.

The control statement if is declared to evaluate if an expression is true. This expression calls a function named login and passes the user’s credentials as its arguments. We can assume that the call to login is doing something like validating the user’s information and registering their request with a server. If the user was successfully logged in, the function will return True. In this case, we can updated our variable user_logged_in to reflect this.

Variables, Values, and Data Types

The first 3 lines in the example above are variable initializations. The first line is username = "test" which instructs our machines to create a new variable named username and assign it the value "test". All variables require memory to store their values. When a variable is created, our machine will assign it an address so that it knows where to access that variable’s value. This concept is rather simple: in order for something to exist, there must be space for it. As Python developers, we will rarely think about where and how these values are being stored.

Most languages have rules about what names we can give to variables, and Python is no exception. A variable can use any combination of letters, numbers, and underscores, as long as it does not start with a number and is not the same as a reserved word.

Reserved words in Python

and continue finally is raise

as def for lambda return

assert del from None True

async elif global nonlocal try

await else if not while

break except import or with

class False in pass yield

Data Types

Different values are represented differently depending on their type. An integer can be represented in binary in a very straightforward manner. 10 in base 10 is represented as 1010 in binary, for example. Characters in a string like "securePass1" are represented using an encoding such as ASCII or Unicode. Real numbers are typically represented as floating-point types using the IEEE 754 Standard for Floating-Point Arithmetic.

When we create a variable in Python, we do not need to explicitly declare what type that variable it is. That is what makes Python dynamically typed. Instead, it will infer the type based on the value. We can always ask Python how it is representing each variable, as seen in the following code.

>>> type("securePass1")

<class 'str'>

>>> type(10)

<class 'int'>

>>> type(3.14)

<class 'float'>

Basic Operators

A programming language would be pretty useless if it did not offer some way to do basic arithmetic. Python supports the following arithmetic operators: +, -, *, /, //, ** and %. You may instantly recognize the first 4, but the last 3 may not be so familiar. Let us start with //, integer division.

An integer data type cannot represent decimal values. So what happens if you try to execute something like 1 / 2? We recognize this to be 0.5, but that is not the case with every programming language. In C, for example, 1 and 2 are treated as integer types by default. If you attempt to evaluate 1 / 2, the result is 0 since there is no way to store the decimal information. Essentially, the decimal portion of the result is truncated.

Python is a little more forgiving. 1 / 2 evaluates to 0.5, as we may expect. However, if you want to perform division between these operands as if they were both integers, you can use //. Indeed, 1 // 2 evalutes to 0 in Python.

The ** operator is more straightforward: it raises the left-hand operand to whatever value is provided on the right side. For example, 2**4 evaluates to 16.

Finally, the modulus operator % provides the remainder of integer division. So something like 5 % 2 would return 1.

Statements and Expressions

A statement is anything that can be executed. This could be a simple variable assignment or a function call.

username = "user1"

print(username == "user1")

An expression is a statement that evaluates into some result. This could be the result of a function call, an assignment, or a complex computation.

y = x**2

get_user_by_id(10)

Basic I/O

Python provides functions to read input from the user’s keyboard as well as print information back to the terminal using input and print. When input is evaluated, it will wait for the user to press Enter before processing the input. If you would like to provide a text prompt to the user before entering, you can pass the prompt as a string.

text = input("Enter some text: ")

print(text)

An example run of this program may look like the following.

Enter some text: OK here it is

OK here it is

Notice that the result of the input function is the actual data entered by the user. This is immediately assigned to the text variable. We can easily print out the value of text by passing it as an argument to the print function.

Formatted Output

We can work with more detailed output using formatted strings, as demonstrated in the following example.

pi = 3.14159265359

print(f"The value of pi is approximately {pi:.3f}.")

Output

The value of pi is approximately 3.141.

More details about the different ways of using formatting strings is documented here.

Commenting Code

The last topic of this introduction is about commenting. Communicating the purpose of your program is not only important when working with others, but you will find it to be extremely helpful as you build larger and larger projects. It is a common trap to dive into an idea with absolute focus, quickly hacking away as your program takes shape. This sort of approach is like a house of cards. As soon as your attention is diverted, it takes time to build that model up in your head again.

Writing down your program’s purpose and design while documenting its function is paramount for a product that is both robust and maintainable. The simplest way to communicate ideas is to leave comments in the code itself. There are two ways to leave basic comments in Python: single-line and multi-line. The code below demonstrates both.

"""

This small code example shows how to comment in Python.

By the way, this is a multi-line comment.

"""

a = "user1" # stores the user's name

As see above, multi-line comments are wrapped in """. These are typically reserved for things like function documentation (more on that later). Single-line comments start with # and can be placed on the same line as a statement.

There is a third type of commenting called self-commenting. The same example above will motivate this type of commenting. There is nothing invalid about the statement a = "user1". It defines a variable named a whose value is the string "user1". However, if there wasn’t a comment on the same line describing its purpose, it might not be so clear. There is an easier way to communicate this without commenting at all. We could instead write something like username = "user1". The variable name itself resolves any ambiguity about its purpose and obviates the need for an additional comment.