Parallel Graph Traversal

Introduction

For an introduction on basic graph theory and traversal algorithms, see these notes.

Parallelization over vertices

When it comes to parallel algorithms, the first thing that may come to your mind is that they must operate on either the edges or the vertices. In either case, it doesn’t take much to imagine that such algorithms will require communication between threads due to dependencies in the graph or traversal algorithm.

In a breadth-first search, all vertices in one level must be explored before moving into the next. The first approach we look at will require multiple calls to the kernel, one for each level.

Top-down Approach

__global__ void bfs_kernel(CSRGraph csrGraph, uint *level,

uint *newVertexVisited, uint *currLevel) {

int vertex = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (vertex < csrGraph.numVertices) {

if (level[vertex] == currLevel - 1) {

for (uint edge = csrGraph.srcPtrs[vertex]; edge < csrGraph.srcPtrs[vertex + 1]; edge++) {

int neighbor = csrGraph.edges[edge];

if (level[neighbor] == UINT_MAX) { // Neighbor not visited

level[neighbor] = currLevel;

*newVertexVisited = 1;

}

}

}

}

}

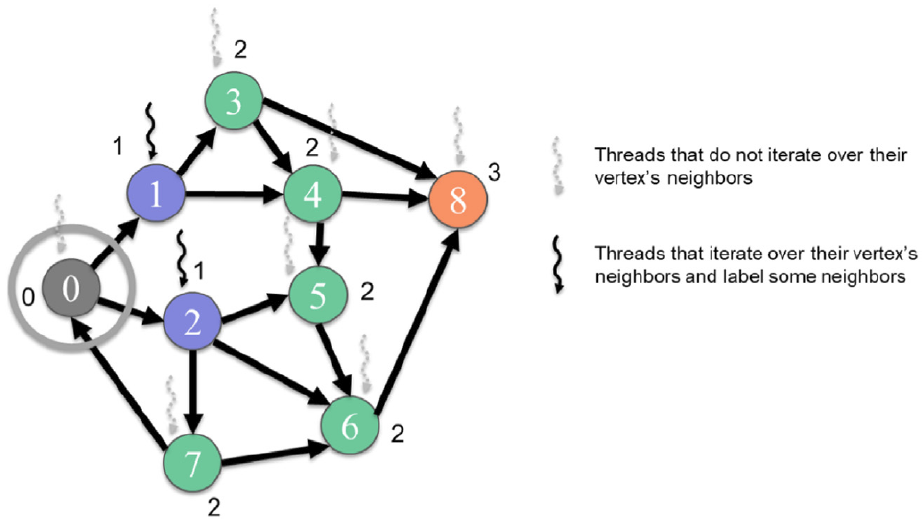

The first kernel above labels the vertices that belong on the given level. For each vertex, it iterates over the outgoing edges. These can be accessed as the nonzero elements in the adjacency matrix for each row. The CSR format is ideal for this case. The figure below shows the result of the first kernel. Only 2 of the threads are active for the first level based on the input graph. This particular version of the algorithm is called the push version.

Figure 1: Vertex-centric push BFS traversal from level 1 to level 2 (Hwu, Kirk, and El Hajj 2022).

The boundary check ensures that the kernel only processes vertices that belong to the current level. Each thread has access to a global newVertexVisited and will set this to 1 if it finds a new vertex to visit. This is used to determine if the traversal should continue to the next level.

Bottom-up Approach

The second kernel is also a vertex-centric approach, except it considers incoming edges rather than outgoing ones. This is called the pull version.

__global__ void bfs_kernel(CSCGraph cscGraph, uint *level,

uint *newVertexVisited, uint *currLevel) {

int vertex = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (vertex < cscGraph.numVertices) {

if (level[vertex] == UINT_MAX) {

for (uint edge = cscGraph.dstPtrs[vertex]; edge < cscGraph.dstPtrs[vertex + 1]; edge++) {

int neighbor = cscGraph.edges[edge];

if (level[neighbor] == currLevel - 1) { // Neighbor visited

level[vertex] = currLevel;

*newVertexVisited = 1;

break;

}

}

}

}

}

Note the use of the Compressed Sparse Column (CSC) format for the graph. The kernel requires that each thread be able to access the incoming edges, which would be determined by the nonzero elements of a give column of the adjacency matrix.

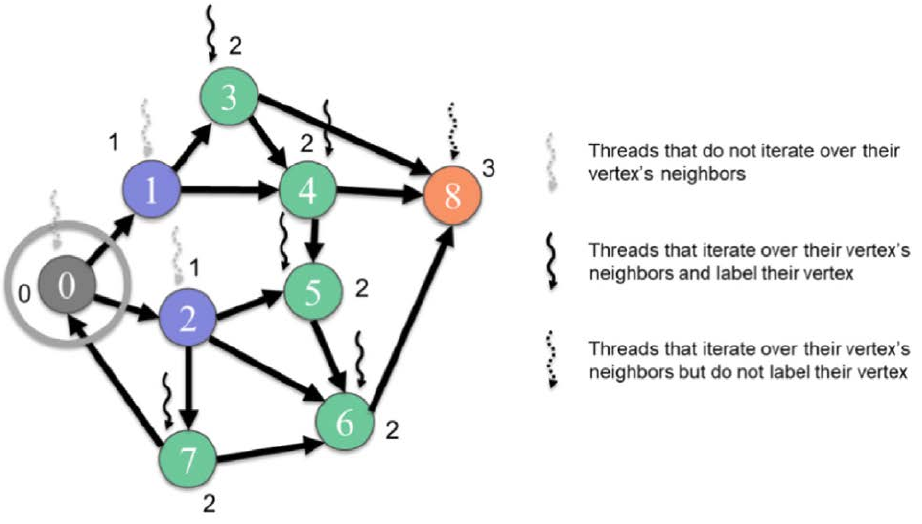

Figure 2: Vertex-centric pull BFS traversal from level 1 to level 2 (Hwu, Kirk, and El Hajj 2022).

From each thread’s point of view, if there is an incoming edge at the previous level then it will be visited at the current level. In that case its job is done and it can break out of the loop. This approach is more efficient for graphs with a high average degree and variance.

In early levels, the push approach is more efficient because they have a relatively smaller number of vertices per level. As more vertices are visited, the pull approach is more efficient because there is a higher chance of finding an incoming edge and exiting early. Since each level is a separate kernel call, both of these can be combined. An additional piece of overhead would be that one would require both CSR and CSC representations of the graph.

Parallelization over edges

As the name suggests, the edge-centric approach processes the edges in parallel. If the source vertex belongs to a previous level and the destination vertex is unvisited, then the destination vertex is labeled with the current level.

__global__ void bfs_kernel(COOGraph cooGraph, uint *level,

uint *newVertexVisited, uint *currLevel) {

int edge = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (edge < csrGraph.numEdges) {

uint vertex = cooGraph.src[edge];

if (level[vertex] == currLevel - 1) {

uint neighbor = cooGraph.dst[edge];

if (level[neighbor] == UINT_MAX) {

level[neighbor] = currLevel;

*newVertexVisited = 1;

}

}

}

}

The edge-centric approach has more parallelism than the vertex-centric approaches. Graphs typically have more edges than vertices, so the largest benefit is on smaller graphs. Another advantage related to load imbalance. In the vertex-centric approach, imbalance comes from the fact that some vertices have more edges than others.

The tradeoff of this that every edge is considered. There may be many edges that are not relevant for a particular level. The vertex-centric approach could skip these entirely. Since every edge needs to be indexed, the COO format is used. This requires more space than the CSR or CSC formats.

Since these sparse representations are already used, we could perform these operations using sparse matrix multiplications. Libraries such as cugraph provide implementations of these algorithms.

Improving work efficiency

The previous two approaches have a common problem: it is likely that many threads will perform no useful work. Take the vertex-centric approach, for example. The threads that are launched only to find out that their vertex is not in the current level will not do anything. This is a waste of resources. Ideally, those threads would not be launched in the first place. A simple solution to this is to have each thread build a frontier of vertices that they visit, so that only the vertices in the frontier are processed.

__global__ void bfs_kernel(CSRGraph csrGraph, uint *level,

uint *prevFrontier, uint *currFrontier,

uint numPrevFrontier, uint *numCurrFrontier,

uint currLevel) {

uint i = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (i < numPrevFrontier) {

uint vertex = prevFrontier[i];

for (uint edge = csrGraph.srcPtrs[vertex]; edge < csrGraph.srcPtrs[vertex + 1]; edge++) {

uint neighbor = csrGraph.dst[edge];

if (atomicCAS(&level[neighbor], UINT_MAX, currLevel) == UINT_MAX) {

uint currFrontierIdx = atomicAdd(numCurrFrontier, 1);

currFrontier[currFrontierIdx] = neighbor;

}

}

}

}

When launched, only the threads corresponding to a frontier will be active. They start by loading the elements from the previous frontier. As before, they iterate over the outgoing edges. If the neighbor has not been visited, then it is labeled with the current level and added to the current frontier. The atomic operation ensures that the size of the frontier is updated correctly.

The call to atomicCAS prevents multiple threads from adding the same vertex to the frontier. It checks whether the current vertex is unvisited. Not every thread is going to visit the same neighbor, so the contention should be low for this call.

Privatization to reduce contention

The use of atomic operations in the previous example introduces contention between threads. As we have previously studied, privatization can be applied in these cases to reduce that contention. In this case, each block will have its own private frontier. The contention is then reduced to atomic operations within a block. An added benefit is that the local frontier is in shared memory, resulting in lower latency atomic operations.

__global__ void bfs_kernel(CSRGraph csrGraph, uint *level,

uint *prevFrontier, uint *currFrontier,

uint numPrevFrontier, uint *numCurrFrontier,

uint currLevel) {

// Initialize privatized frontier

__shared__ uint currFrontier_s[LOCAL_FRONTIER_CAPACITY];

__shared__ uint numCurrFrontier_s;

if (threadIdx.x == 0) {

numCurrFrontier_s = 0;

}

__syncthreads();

// Perform BFS

uint i = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (i < numPrevFrontier) {

uint vertex = prevFrontier[i];

for (uint edge = csrGraph.srcPtrs[vertex]; edge < csrGraph.srcPtrs[vertex + 1]; edge++) {

uint neighbor = csrGraph.dst[edge];

if (atomicCAS(&level[neighbor], UINT_MAX, currLevel) == UINT_MAX) {

uint currFrontierIdx_s = atomicAdd(&numCurrFrontier_s, 1);

if (currFrontierIdx_s < LOCAL_FRONTIER_CAPACITY) {

currFrontier_s[currFrontierIdx_s] = neighbor;

} else {

numCurrFrontier_s = LOCAL_FRONTIER_CAPACITY;

uint currFrontierIdx = atomicAdd(numCurrFrontier, 1);

currFrontier[currFrontierIdx] = neighbor;

}

}

}

}

__syncthreads();

// Allocate in global frontier

__shared__ uint currFrontierStartIdx;

if (threadIdx.x == 0) {

currFrontierStartIdx = atomicAdd(numCurrFrontier, numCurrFrontier_s);

}

__syncthreads();

// Commit to global frontier

for (uint currFrontierIdx_s = threadIdx.x; currFrontierIdx_s < numCurrFrontier_s; currFrontierIdx_s += blockDim.x) {

currFrontier[currFrontierStartIdx + currFrontierIdx_s] = currFrontier_s[currFrontierIdx_s];

}

}

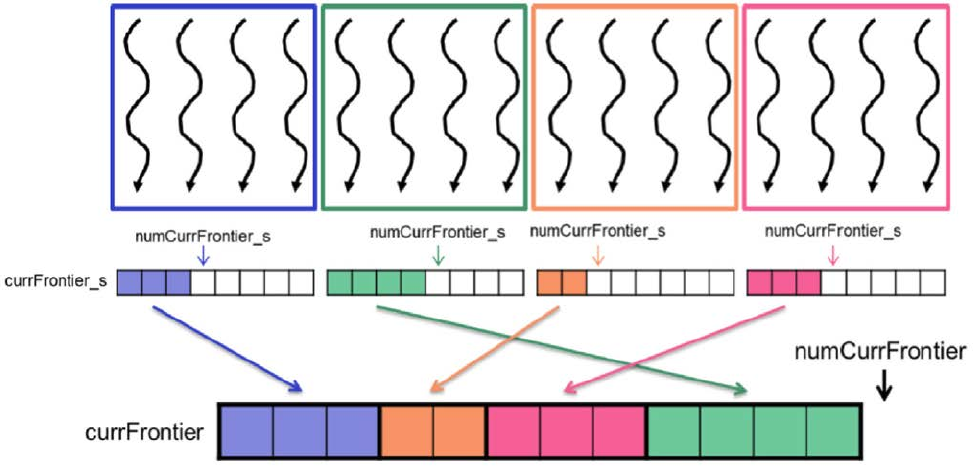

The main BFS block of the kernel above will write to the local frontier as long as there is space. If the capacity is hit, all future writes will go to the global frontier.

After BFS completes, a representative thread (index 0) from each block will allocate space in the global frontier, giving it a unique starting index. This allows each block to safely write to the global frontier without contention. The figure below shows the result of the privatized frontier.

Figure 3: Privatized frontier for BFS traversal (Hwu, Kirk, and El Hajj 2022).

Additional Optimizations

Reducing launch overhead

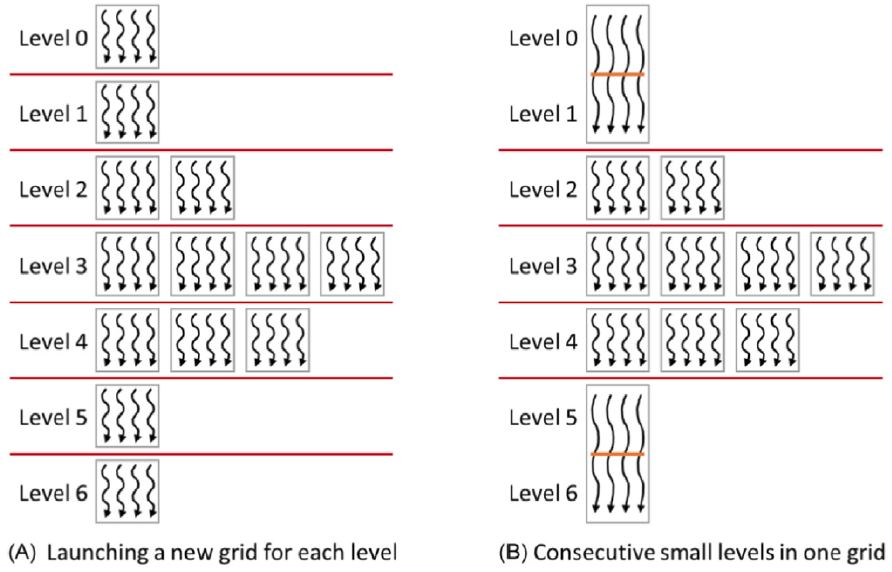

If the frontiers of a BFS are small, the overhead of launching a kernel for each level can be significant. In such cases, a kernel with a grid size of 1 can be launched to handle multiple levels. This block would synchronize after each level to ensure that all threads have completed the current level before moving on to the next.

Figure 4: Reducing launch overhead by handling multiple levels in a single kernel (Hwu, Kirk, and El Hajj 2022).

Improving load balance

In the first vertex-centric approach we looked at, the threads were not evenly balanced due to the fact that some vertices have more edges than others. For graphs that have high variability in the number of edges per vertex, the frontier can be sorted and placed into multiple buckets. The buckets would be processed by a separate kernel.