Pretraining Large Language Models

These notes provide an overview of pre-training large language models like GPT and Llama.

Unsupervised Pre-training

Let’s start by reviewing the pre-training procedure detailed in the GPT paper (Radford et al. 2018). The Generative in Generative Pre-Training reveals much about how the network can be trained without direct supervision. It is analogous to how you might have studied definitions as a kid: create some flash cards with the term on the front and the definition on the back. Given the context of the word, you try and recite the definition. For a pre-training language model, it is given a series of tokens and is tasked with generating the next token in the sequence. Since we have access to the original documents, we can easily determine if it was correct.

Given a sequence of tokens \(\mathcal{X} = \{x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n\}\), the model is trained to predict the next token \(x_{n+1}\) in the sequence. The model is trained to maximize the log-likelihood of the next token:

\[\mathcal{L}(\mathcal{X}) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \log p(x_{i+1} \mid x_{i-k}, \ldots, x_i)\]

where \(k\) is the size of the context window.

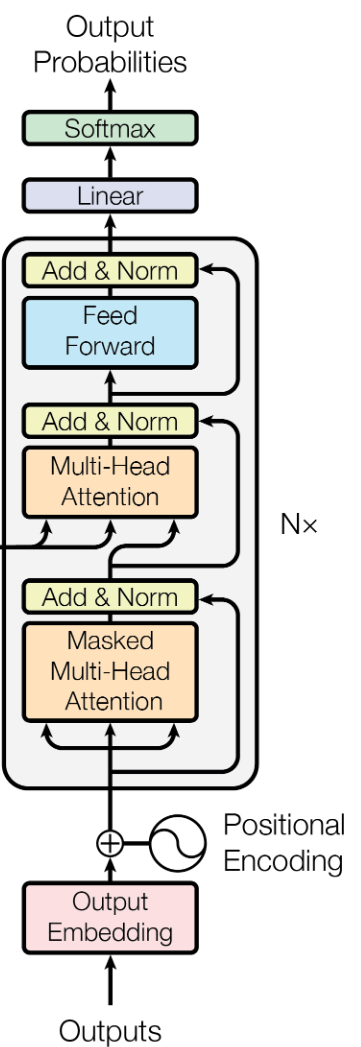

Large language models are typically based on the Transformers model. The original model was trained for language translation. Depending on the task, different variants are employed. For GPT models, a decoder-only architecture is used, as see below.

Figure 1: Decoder-only diagram from (Vaswani et al. 2017).

The entire input pipeline for GPT can be expressed rather simply. First, the tokenized input is passed through an embedding layer \(W_{e}\). Embedding layers map the tokenized input into a lower-dimensional vector representation. A positional embedding matrix of the same size as \(\mathcal{X} W_{e}\) is added in order to preserve the order of the tokens.

The embedded data \(h_0\) is then passed through \(n\) transformer blocks. The output of this is passed through the softmax function in order to produce an output distribution over target tokens.

Supervised fine-tuning

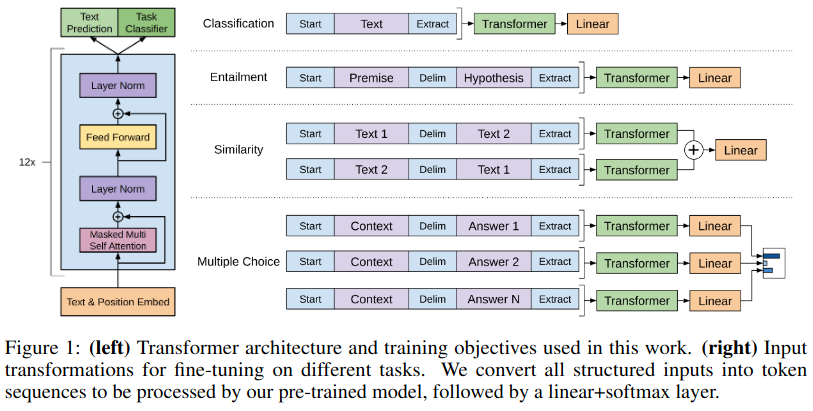

Given a model pre-trained using the above method, it is then fine-tuned for different tasks. The input and loss functions used are task-specific. In general, the text was formatted in a way that matches the task. The figure below shows the different tasks used.

Figure 2: Figure 1 from (Radford et al. 2018).

Story Cloze Test

This test evaluates commonsense reasoning by asking models to choose the correct ending for a story from two options. This is evaluated using a standard accuracy metric.

General Language Understanding Evaluation (GLUE)

GLUE is a multi-task benchmark that evaluates models on a variety of natural language understanding tasks, including sentiment analysis, textual entailment, and question answering. Textual entailment involves determining the relationship between two sentences: a premise and a hypothesis.

RACE (Reading Comprehension)

A datset of multiple-choice reading comprehension questions. The model is tasked with selecting the correct answer from four options.

Semantic Similarity Tasks

Datasets like Microsoft Research Paraphrase Corpus (MRPC) were used to determine whether two sentences are paraphrases. Another dataset, Quora Question Pairs (QQP) tasks the model with identifying duplicate questions. Finally, the Semantic Textual Similarity Benchmark (STS-B) measures sentence similarity on a continuous scale.

Zero-shot Behaviors

The authors show that the model exhibits some reasonable performance on tasks even before the fine-tuning process. They show that the relative performance on these tasks increases with the amount of pre-training. This is known as zero-shot learning.

From GPT to GPT2

GPT2 is a larger version of GPT, with an increased context size of 1024 tokens and a vocabulary of 50,257 vocabulary. In this paper, they posit that a system should be able to perform many tasks on the same input. For example, we may want our models to summarize complex texts as well as provide answers to specific questions we have about the content. Instead of training multiple separate models to perform these tasks individually, the model should be able to adapt to these tasks based on the context. In short, it should model \(p(output \mid input, task)\) instead of \(p(output \mid input)\).

The model itself is not explicitly trained to perform any of these tasks. The authors show that it can still perform better on a specific task by adding the context into the prompt. This is known as zero-shot learning. For example, if you want to generate a summary for a document or other textual context, you can append “TL; DR” to the prompt.

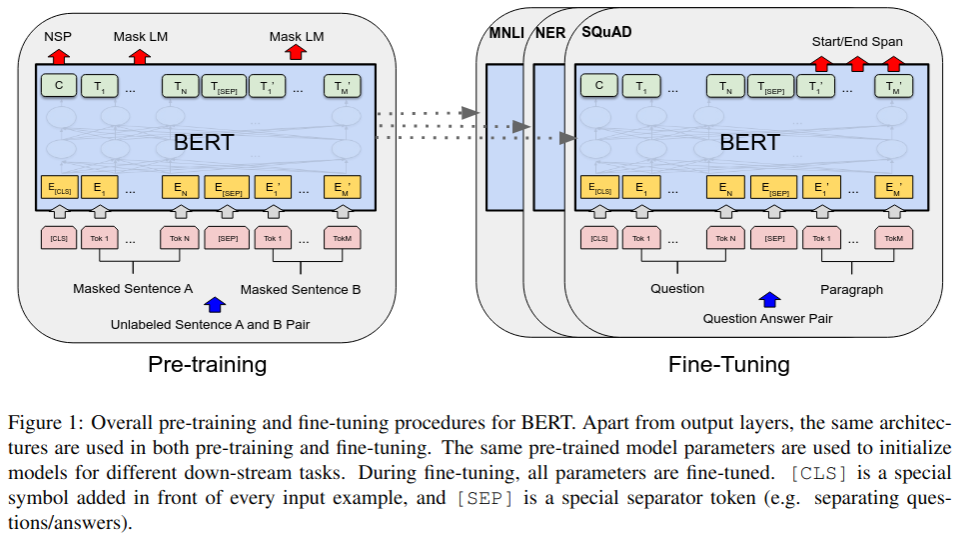

BERT

BERT is a bidirectional transformer model that is trained using a masked language model objective (Devlin et al. 2019). The model is trained to predict masked words in a sentence. This is in contrast to GPT, which is trained to predict the next word in a sentence.

Figure 3: BERT model architecture from (Devlin et al. 2019).

Pre-training

Two separate tasks are used to pre-train BERT: Masked LM (MLM) and Next Sentence Prediction. In MLM, some percentage of the input is masked at random. The model must predict the masked words. In the Next Sentence Prediction task, the model is given two sentences and must predict whether the second sentence follows the first. This is framed as a binary classification task. The authors shows that this second task was especially helpful to both QA and NLI tasks.

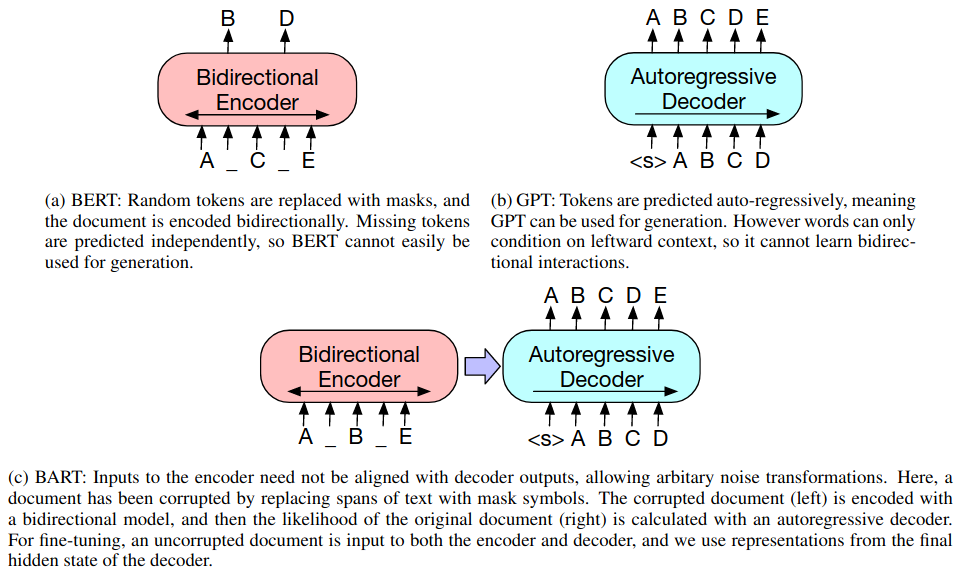

BART

Models like BERT are encoder models for predictive modeling tasks whereas decoder architectures like GPT are used for generative tasks. BART takes an encoder-decoder approach to pre-training (Lewis et al. 2019).

Pre-training

The pre-training task in BART is to add arbitrary noise to the input and have the model reconstruct the original text. The figure below shows a comparison between BERT, GPT, and BART.

Figure 4: Comparison of BERT, GPT, and BART from (Lewis et al. 2019).

GPT3

The approach to GPT3 was to take GPT2 as a starting point and scale up (Brown et al. 2020). The number of parameters are increased from 1.5 billion to 175 billion. The dataset preparation, training details, and evaluations are mostly the same.